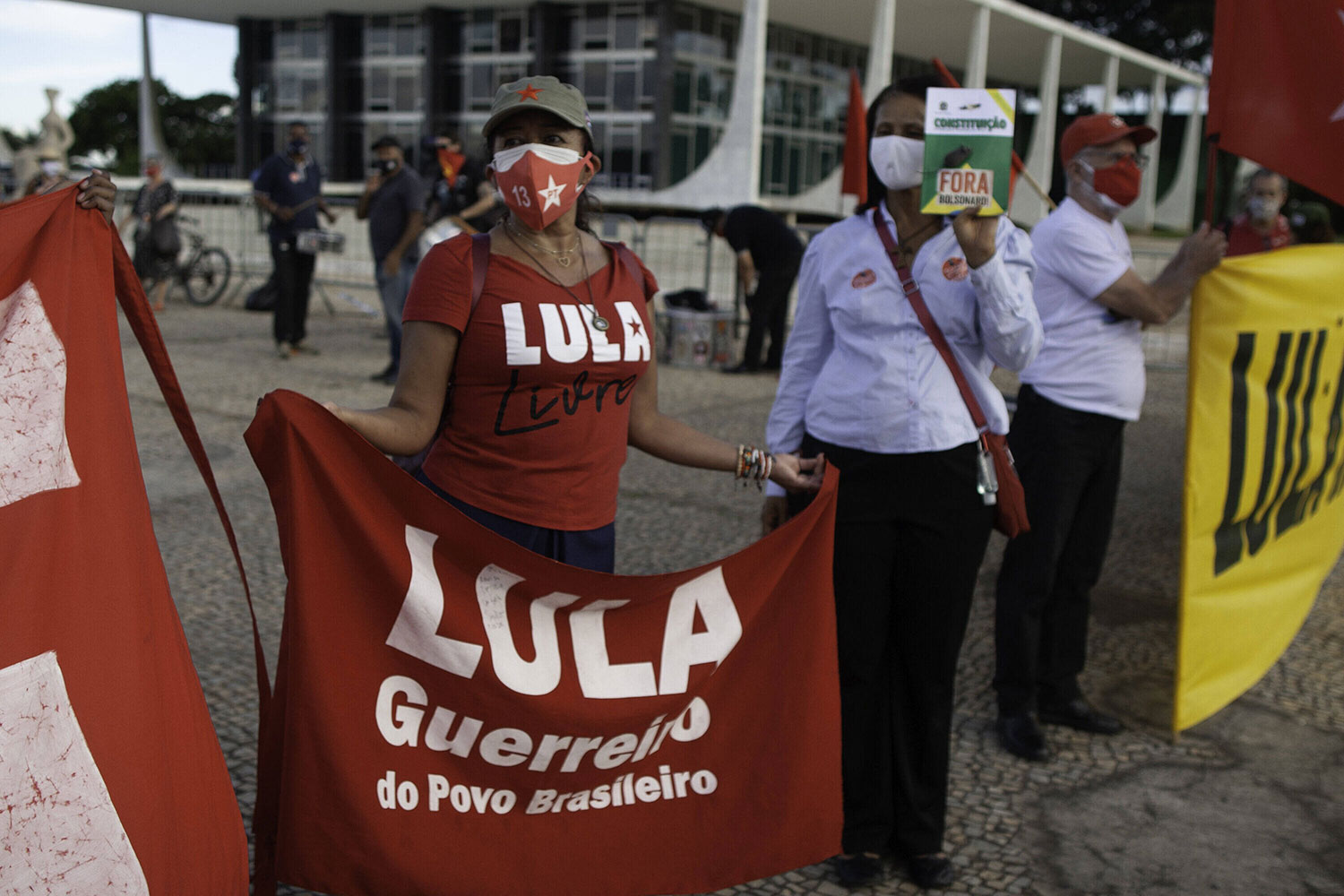

Since the annulment of former Brazilian President Lula’s corruption conviction, polls indicate that a united-left front with Lula as candidate could defeat conservative President Bolsonaro in the 2022 elections.

Rael Almonte Reyes, 26 April 2021

March 8, 2021 saw a colossal earthquake for Brazil’s political echelons. The Brazilian Supreme Court’s decision to annul Luiz Inacio “Lula” da Silva’s corruption conviction, which will allow him to run in the 2022 general election, has serious implications on the race for President. Prior to this decision, the leftist opposition party, the Partido dos Trabalhadores (Workers Party; PT), was struggling to pose a coordinated challenge to controversial far-right President Jair Bolsonaro’s re-election. Polls indicate that Lula will likely secure significant support in the first round of the 2022 general election, but this will mean nothing unless he can organize a united left-front against Bolsonaro in a second round.

The most recent presidential election polarized Brazil as it happened during the peak of Operation Car Wash, an investigation into corruption all over Brazil and aimed at leaders from the country’s largest parties. After Lula was sentenced to 12 years in prison on charges related to Operation Car Wash, Fernando Haddad, a close ally of the former President, became PT’s candidate for the Presidency. Haddad’s lack of recognition, the diminishing popularity of PT and its allied parties due to the increasing number of corruption convictions, and Lula’s delayed conviction which forced PT to keep Lula as the candidate until last minute were some of the factors that ensured Haddad’s loss.

President Jair Bolsonaro, a former army captain and congressman representing Rio de Janeiro, won the 2018 election in a run-off by championing anti-LGBTQ+ and anti-abortion policies as well as “tough on crime” laws that appealed to religious zealots and the conservative middle class. As polls conducted prior to the 2018 election indicated that the increase in crime was a top issue for Brazilian voters, his “tough on crime” platform coupled with his proposals to loosen restrictions that prohibit the purchase and use of firearms secured his election as President in the second round.

The day after Bolsonaro was elected President, he nominated Judge Sergio Moro, who presided over the sentencing of Lula and other politicians during Operation Car Wash, to be Minister of Justice and Public Security. Moro’s nomination as Minister gave credence to the criticism from civil society and the opposition that the investigation and subsequent sentencing were unfairly targeting the President’s primary opponents in order to secure Bolsonaro’s victory. These groups were vindicated when Brazil’s Supreme Court ruled that Sergio Moro had acted in a biased manner in sentencing Lula. The court used leaked messages which showed collusion between Moro and prosecutors that, when coupled with the apparent quid pro quo of Moro being appointed Minister of Justice and Public Security, allowed Lula’s defence to argue for the sentence to be annulled.

The Supreme Court’s decision had an immediate effect on the projected outcome of the 2022 general elections. Election polls for the 2022 presidential race show Lula becoming the front runner after his sentence was annulled. In a first round, three different polls show Lula beating Bolsonaro 31.2-30.7, 34-30, and 29-28. More importantly, the results of the same three polls were replicated in a second round, which indicates that Lula could unite the left against Bolsonaro. Lula’s strong showing in polls of the second round are important as Brazil’s fractured political scene makes it virtually impossible for a candidate to win the necessary 50 percent majority required to be elected president in a first-round election. This is great news for PT and its traditionally allied leftist parties, who prior to the sentence’s annulment were trailing Bolsonaro by a significant margin.

Lula’s amicable relationship with the plethora of left-wing parties in Brazil will be important during the second round of the 2022 election. While PCdoB (the Communist Party of Brazil) aligned itself with PT, PDT (Democratic Labour Party; Centre-left) and PSOL (Socialism and Liberty Party; left-wing) did not. The lacklustre support for Haddad, while not the primary reason for the loss in 2018, certainly did not help the already embattled party. Now the situation is different, as evidenced by the alliances made during the 2020 municipal elections. In Sao Paulo, the PSOL candidate received significant support from Lula and Ciro Gomes of the PDT, which is noteworthy as the PSOL came into existence as a splinter from the PT. Ultimately, we will probably see an anti-Bolsonaro coalition form around which ever left-wing candidate goes to the runoff – the most likely candidate being Lula.

All of the left-wing politicking is overshadowed by the spectre of Bolsonaro, who praises the country’s former military dictatorship. Coupled with his credentials as a former member of the armed forces, this earned the President significant support from the military, which could prove instrumental in the event Bolsonaro decides to take draconian measures against his left-wing detractors. This support has already manifested itself in anti-democratic ways: Eduardo Villas Boas, the former head of the Armed Forces, admitted that he and other members of the military brass attempted to pressure the Supreme Court before they ruled on the case against Lula in 2018.

The stakes are high for the opposition as Bolsonaro supports those who yearn for a return to the military dictatorship. In April 2020, President Bolsonaro joined a pro-dictatorship rally, proclaiming “The era of roguery is over. Now it’s the people who are in power.” An anti-democratic shadow looms over the upcoming general elections, but the die has already been cast: will Bolsonaro drag Brazil back to the 1960s, or will Brazil choose democracy and progress into the 21st century?