Global supply chains featuring commodity ingredients and foods are often opaque, tangled and secretive. Huge multi-national food companies often have well-crafted human rights policies listed on their websites while at the same time finding themselves in legal conflict. This is often over payment and treatment of workers producing the basic building blocks of the many products from chocolate bars sold in supermarkets to the latest mobile phone. It’s a murky world, and one that is attracting the attention of Washington DC, the United Nations and the EU.

Bruce McMichael

30 June 2023

Chinese version | French version | Spanish version

Reverse engineer a 1kg block of chocolate ready to be melted and tempered into the chocolate bars ready for public consumption, and you’ll find cocoa paste made from cocoa beans, picked in tropical regions and countries such as West Africa, Indonesia, Brazil and Colombia.

Cocoa from West Africa, avocadoes from southern California, and tomato crops from Calabria, south Italy, have all been linked to child labor and even exploitation through forced labor. In May 2022, a group of United Nations human rights experts supported adopting the Durban Call to Action on the Elimination of Child Labor by representatives of governments, workers’ and employers’ organizations, UN agencies, civil society and regional organizations attending the 5th Global Conference on the Elimination of Child Labor in South Africa. It’s an issue reaching the highest levels of international civil society and government.

On June 1 the EU Parliament passed the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD) which will require large corporations who sell their products in the EU to comply with CSDDD checks on suppliers. Supplier caught using child labor or damaging the environment will face sanctions. The EU is committed to SDG Target 8.7 calling for an end to child labor in all forms by 2025.

Chocolate and its principal ingredients, cocoa and sugar, have a long and complex history. Cocoa is a commodity crop and a significant revenue generator for many countries in the Global South. Indeed, in Brazil sugar is often referred to as a ‘hunger crop’. Processing and marketing cocoa into chocolate is primarily done in wealthy industrialized nations such as Belgium, the US and the UK. Ultimately, this trading and economic imbalance puts cocoa-producing countries at a disadvantage and vulnerable to market conditions. This feeds down to the estate workers. Their already low incomes fluctuate, often leaving them hungry out of harvesting season.

Across West Africa, cocoa is traditionally grown on smallholdings and family farms. Many cannot afford to employ outside workers and so turn to local children. Some are family, others not. They are often found in non-hazardous roles, but not always. When this work interrupt schooling, it is classified as child labor and is at odds with the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, which designated 2021 as the International Year for the Elimination of Child Labor. However, many cocoa harvesting families do not recognize their use of children as slave labor but rather as a time-served method of securing free work in support of the family income. However, this is generally not ‘forced’ labor, which involves coercing workers against their will, often with the threat of violence.

Cocoa is one of chocolate’s main ingredients, derived from the ‘beans’ (seeds) of the Cocoa Theobroma tree. A milk chocolate bar will typically contain a sugar content from 2 to 55%, primarily obtained from Saccharum genus grasses. This accounts for 10% to 99% of the total product, depending on the quality and retail price. Other common ingredients include soy lecithin, flavours such as vanilla, fruits and nuts, and milk and white chocolate products.

The issue came to law makers’ attention in Washington DC in June 2022 when a long-running US child slavery lawsuit involving global supply chains operated by Hershey, Nestle and Cargill in the Côte d’Ivoire was dismissed by a federal judge. Other defendants in the trial included Mars Inc, Mondelez International, Barry Callebaut and Olam International. US District Judge Dabney Friedrich rejected the case on the grounds the plaintiffs could not prove a ‘traceable connection’ between the seven defendants and the specific cocoa farms where they worked.

Many pan-national advocacy organisations are also taking an interest in the issue. The World Fair Trade Organization stands by ten guiding principles, including good working conditions and ensuring no forced labor is used to manufacture any product. The organization also adheres to the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child and national and local law on the employment of children.

Agencies and NGOs such as the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations (FAO), Oxfam and the Global Citizen’s Initiative all research and publish work on this topic.

The Swiss-based International Cocoa Initiative (ICI) includes representatives of the International Labor Organization (ILO), the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner on Human Rights (OHCHR), and UNICEF on its advisory board. ICI is a non-profit foundation that ‘works to ensure a better future for children in cocoa-growing communities’.

In a 2021 report by Oxfam, there is talk of a ‘dirty little secret about the chocolate industry’. That secret, notes Oxfam, references the international chocolate industry’ profits gleaned from child labor and enslavement’. In 2021, the ICI calculates that 1.6 million children were employed as ‘slave labor’ across Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana. The ICI estimate (2021) that 152 million children work in child labor, and of that 70% are employed in agriculture.

A 2015 report from Tulane University and the US Department of Labor reported that local cocoa farmers employed two million children in ‘hazardous’ conditions across Ghana and the Ivory Coast.

Hazardous working practices and conditions include:

- Land clearing (controlled burning)

- Using sharp tools to harvest the beans

- Carrying heavy loads (bags of cocoa beans)

- Using pesticides.

Harvesting is seasonal, and organizations such as the ICI are tailoring solutions to support targeting interventions and protective monitoring periods when children are at most risk of exploitation.

Founded in 2005 by a group of Dutch journalists, Tony’s Chocolonely has shown that it is possible and profitable to sell chocolates without employing child and slave labor. It is a good example of how to supply the global demand for chocolate in a humane way. Before founding the company, the journalists worked on the Dutch TV news show ‘Keuringdienst van Waarde’ and were involved in an investigation focussing on illegal child labor and modern slavery in the world’s cocoa industry. Its brightly packed chocolates are now widely available.

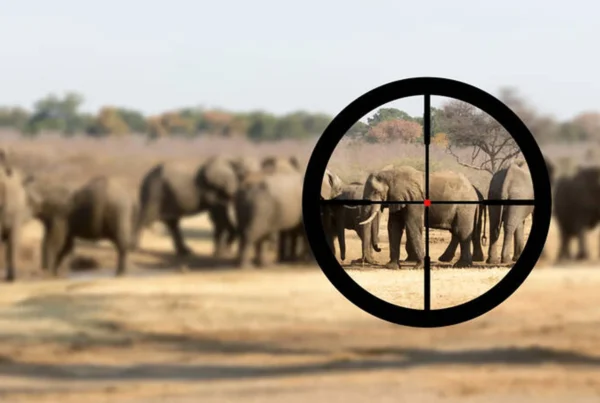

Cocoa is not alone among primary products that have attracted the attention of global human rights advocates. So-called blood or conflict diamonds from countries such as Angola, Liberia and Sierra Leone and cobalt mined in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) for the booming rechargeable battery industry are also linked to child and forced or slave labur. According to Amnesty International, child and forced labor can be found across palm oil plantations in Indonesia.

Palm oil is a cheap and versatile edible oil and a key ingredient in products ranging from chocolate bars to biscuits and breakfast cereals. The US Department of Labor lists products such as carpets, sugarcane, tin and tomatoes made and grown using forced labor. The department publishes the list as ‘a valuable resource for researchers, advocacy organizations and companies wishing to carry out risk assessments and engage in due diligence on labor rights in their supply chains’.

Civil society, governments, chocolate processors and marketers are working to increase awareness of the issue of child/slave labor. Seeking to improve education opportunities and support farm diversification away from cocoa production is one direction that the industry is taking to improve the lives and chances of those working to supply us with chocolate snacks and treats eaten far away from the forests and farms of West Africa and cocoa beans picked by children who should be receiving an education.