This past decade has seen a rising power to challenge US global hegemony. While Chinese investments in Latin America have certainly increased drastically during this period, a closer look into the nature and structure of these investments questions the notion that these investments will translate into substantive dominion over these countries, as is often claimed.

Rael Almonte Reyes, 18 May 2022

The United States pullout from Afghanistan has been interpreted in many ways. Some see it as a grave mistake, some see it as a late, but welcome, correction to a mistake, but all agree on one thing: Pax Americana is over. Since the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, the United States effectively policed the world as the sole superpower, using its soft power when possible and hard power when necessary. This past decade has seen a rising power to challenge U.S. global hegemony: China. Chinese investments in strategically important regions have always made the old guard of American exceptionalism particularly nervous.

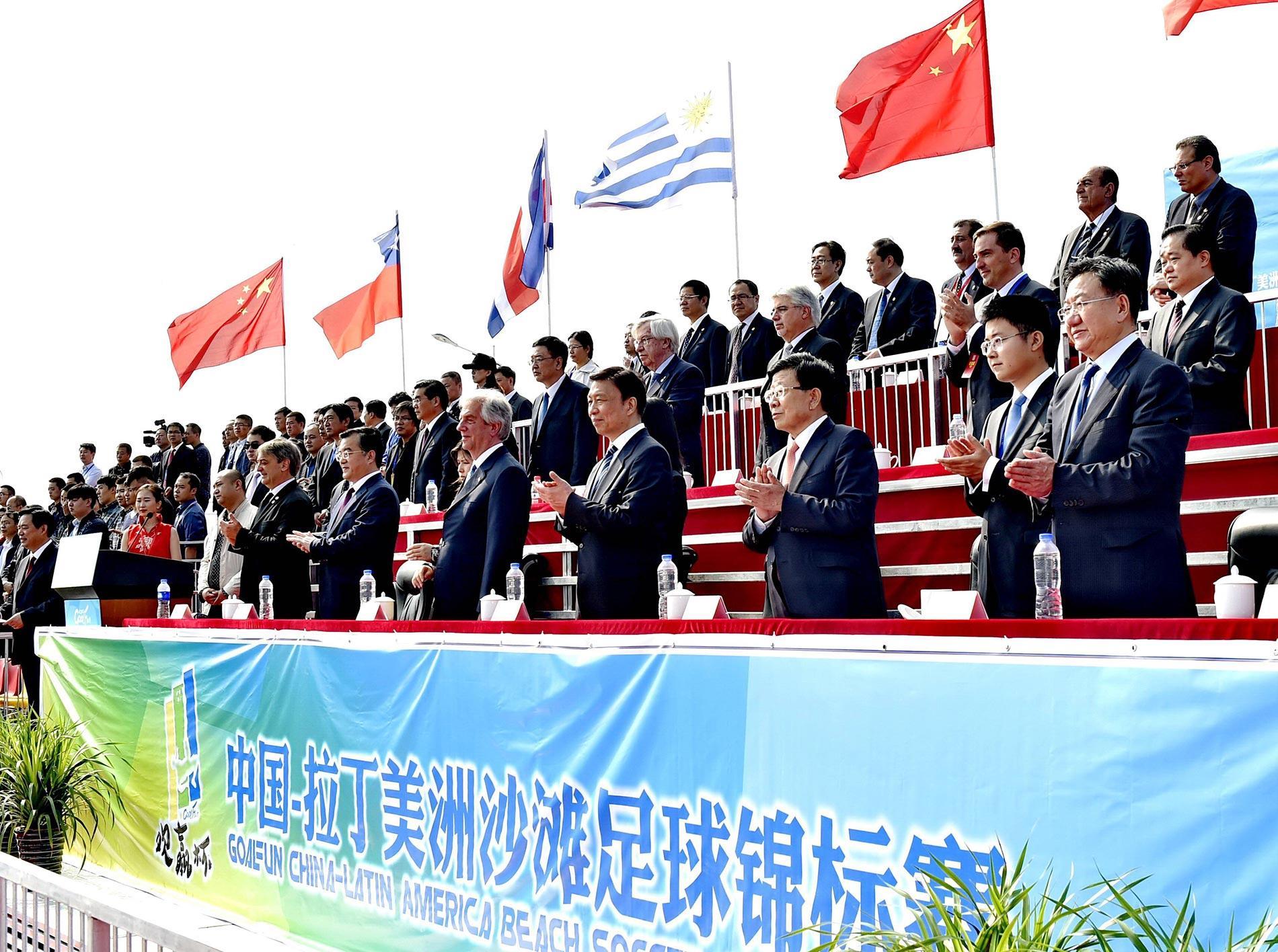

These nervous attitudes turned to outright hostility during the Trump administration, particularly in Latin America and the Caribbean. Chinese investments in the Latin American republics, and their subsequent recognition of the People’s Republic of China over Taiwan, has been of particular interest for analysts in the United States and Europe. While Chinese investments in the region have certainly increased drastically in the past decade, a closer look into the nature and structure of these investments questions the notion that these investments will translate into substantive dominion over these countries, as is often claimed. Ultimately, these investments, most of which are part of its Belt and Road Initiative, often point to China securing natural resources for its ever-expanding economy, with the only political demand being the often-symbolic recognition of its claim to Taiwan being part of “one China”.

First and foremost, it is important to highlight the political aspect of Chinese-Latin American relations. A 2016 Chinese Policy Paper on Latin America and the Caribbean lays out a plethora of areas in which the Chinese could deepen their relations with the Latin American republics, including economic, political, military and cultural affairs. With the exception of some political support in International Organizations and deepening economic ties, very little of the paper has, and likely ever will, be executed. The military aspect has been of particular emphasis in analyses from the U.S. and Europe. The possibility of the Chinese using military and intelligence networks in Latin America to attack American interests has been repeatedly exaggerated to whip up anti-Chinese sentiments in the U.S. Of course, these claims of Chinese military domination in Latin America are inflated to say the least. While China has scaled up the sale of military equipment to Venezuela, Ecuador and Bolivia, the United States still operates 76 military bases in the region and the Fourth Fleet patrols Latin America’s waters. Of course, this military presence is only complimented by the strength of American diplomatic and intelligence networks in the region.

The crux of Chinese influence in the region comes from its deepening of economic relations, particularly in states with abundant natural resources. According to a 2021 IMF Working Paper titled “Chinese Investment in Latin America: Sectoral Complementary and the Impact of China’s Rebalancing”, the percentage of total Chinese Foreign Direct Investment into Latin America has indeed increased over the past decade, peaking at around 21.4% in 2017, an increase from 12% in 2012. These investments have been overwhelmingly focused on resource extraction, although more recently these investments have begun to shift towards manufacturing and services such as electricity, transportation infrastructure and financial services.

While this may paint a picture of a rising power aiming to replace the US as the regional hegemon, the closer one looks into where and what these investments are, the more one begins to understand their targeted nature. In Chile, Chinese trade now accounts for 38.2% of the country’s exports, trumping 16.5% exports to the United States. The vast majority of these exports, 69% according to the Observatory of Economic Complexity (OEC), are raw and refined copper ores. This has been coupled with the acquisition of electric utilities and investments into transportation infrastructure, which begins to paint a picture of a global power building the infrastructure to facilitate the extraction and delivery of resources for its domestic manufacturing sectors.

In Mexico one can see the same process as in Chile, where China is starting to become one of the country’s biggest and most important trade partners. As with Chile, most of Mexico’s exports, 34.6% according to the OEC, are mineral ores and fossil fuels. Exports to China are likely to drastically increase over the next few years as Mexico has granted an exception to a Chinese-owned company to mine lithium despite the state’s plans to nationalize lithium mines. Lithium is a key component in the production of long-lasting electric batteries and therefore a highly coveted resource in the technology sectors of advanced economies. Similar Chinese investment schemes, albeit under differing circumstances, can be discerned in Brazil and Venezuela, which possess the largest mineral wealth in Latin America. Both countries have found huge markets for their crude petroleum in China, and China invests heavily in the infrastructure of these countries to facilitate the extraction of these resources.

Ultimately, it is important to keep in mind that, as of now, Chinese investments are predominantly mutually beneficial. Countries with large mineral reserves and lackluster infrastructure often gain massive markets and the means to export their natural resources, while the Chinese gain cheap and plentiful raw materials to fuel their ever-growing economy. However, there is an important point to be made about this relationship: it is reminiscent of the region’s colonial economic structure. In this relationship, the colonizer would build the roads, ports and other infrastructure necessary to transport mineral wealth back to the “motherland”. The process benefitted a few well-connected sectors of the economy, often exporters and the “middleman” merchants, with few governments choosing to invest in public services such as education, healthcare and security to provide for and support the welfare and socio-economic mobility of their populations. Regardless of this economic relationship, Chinese involvement in the region is dissimilar to an empire eclipsing another, and more akin to a rapidly growing economy attempting to secure natural resources.