Food and agriculture NGOs, think tanks and activists are angry about COP26 negotiations ignoring the environmental consequences of our food systems. After two weeks of heated negotiations, COP26 faces accusations of watering down climate goal ambitions and of delaying finding real solutions. The final COP26 agreement worries climate activists and climate-vulnerable nations.

By Bruce McMichael 24.11.2021

COP26, the UN-sponsored conference hoping to build consensus on how to tackle the impact of climate change, ended on 12 November. To the casual observer the Glasgow-centered conference was a stream of tightly written, well-rehearsed speeches in which the world’s political leaders and senior NGO officials reel off statistics about global rising temperatures, climates change migrants from across Africa and India and about the perilous future that we and our planet face unless the rise in global warming can be dramatically slowed.

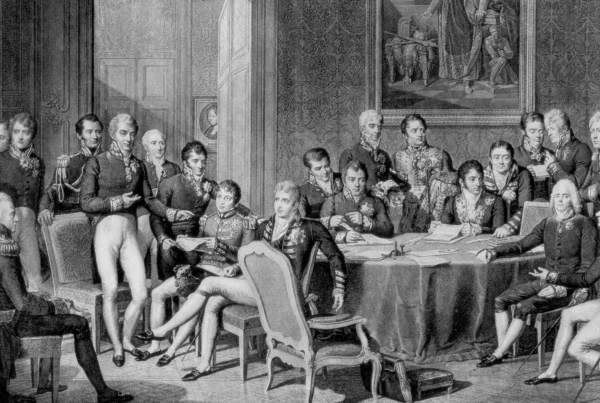

This latest COP (Conference of the Parties) iteration follows the groundbreaking 2015 Paris Agreement, signed by over 190 countries. To summarise, it states the need to limit rising global temperatures to well below 2°C, with the goal of keeping global warming to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels.

The vision for COP26 was to maintain the momentum for the implementation of the Paris Agreement. If Paris was all about ‘let’s do it’, Glasgow was ‘how to do it’. To date, food production accounts for about 30% of greenhouse gas emissions and 40% of land use.

Agreement was reached 24 hours after the conference was scheduled to finish after a flurry of last-minute meetings and compromise. The deal is an important step on the road to staving off the worst effects of the predicted climate change. Indeed, the Glasgow Climate Pact is the first such agreement to explicitly seek a reduction in coal usage, the fossil fuel that causes the greatest release of greenhouse gases. However, at this stage the pledges don’t go far enough to limit global temperatures rise to 1.5C by 2050.

And while plenty of resolutions and issues ranging from finance, local communities, indigenous peoples, and ocean-based actions were included in the final agreement, there were no mentions of food production or agriculture. In addition, although energy issues and transport were dedicated full days during the two-week conference discussions and insight, food and agriculture were left to small breakout sessions organised by civil society and NGOs.

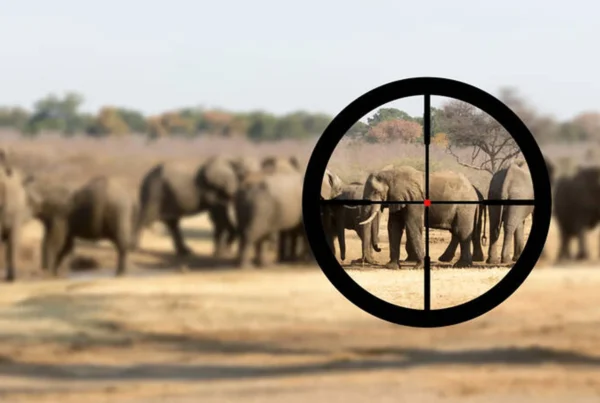

The road from Paris to Glasgow travels through the farm gate. Governments have been slow to invest in transitioning the food and farming sectors away from being emitters of climate change gases such as methane. State-led investment in both sectors is significantly behind the clean energy transition, for example subsidies offered to the wind power industry. According to the UN, the major issues affecting global food systems and the climate are around deforestation (land is used to grow soy, primarily for animal feed), and the use of nitrogen fertiliser, which produces potent greenhouse gas nitrous oxide.

Numerous NGOs and representatives of civil society took part in sideline debates calling for changes in global food production, logistics and consumption, which make up the global Food System, to address climate change. Danielle Nierenberg, president of the US-based non-profit Food Tank says: “This is our chance to connect the dots between our food systems, our health, and the future of the planet”.

However, many outside the main negotiating tent felt those inside didn’t sufficiently consider food as a central tenet, but rather as a series of commodities to be produced at scale in monocultures assisted by new technology and artificial fertilisers and pesticides. Many worry this makes farmers over dependent on large multinational companies and their patents, for example on seeds and animal genetics.

Geoff Tansey, curator of the UK-based online Food Systems Academy, says “There needs to be a greater emphasis on fair, healthy and sustainable food systems and not just farming. Such systems are both biologically and culturally diverse and respect people’s aspirations of (particularly those in developing countries and economies), have sustainable and healthy diets and build on our growing understanding of how ecosystems work.”

Local food supporters such as the Slow Food organisation see COP26 as divided between optimism and distrust. Inside the pavilion a lot of energy from government officials, climate change bureaucrats were working to find agreement between the various countries, while outside the official areas many from civil society and activists noisily protested. Climate change activists including Greta Thunberg gathered lot of supports for anti-COP26 sentiment claiming such meetings were little more than giant ‘green-washing machines.

One of the events organised at COP26 was about ‘Accelerating a just rural transition to sustainable agriculture’. For groups such as Slow Food, such transition must be based on managing biodiversity, agroecology and social justice, and not solutions depending on new technology. Climate change and biodiversity loss must be tackled together; they are closely interlinked problems.

Tansey agrees. Agroecology and delivering better “soil health is vital if food systems are to thrive,” he says, and argues that productive land is not given over to non-food uses such as growing timber or for installing solar panels.

There is a general feeling among farmers from small-scale producers from Africa to western Europe that food systems are cracked and broken – with the way we produce and consume cheap, over subsidised foodstuffs is driving climate change, deforestation and nature loss.

However, while the response to COP26 was mixed at best, it was positive to see several sessions dedicated to understanding what we need to do to fix our food systems: support sustainable farming practices and promote healthy diets that are accessible for all, while benefiting the environment. It would be a very welcome step forward if the next scheduled COP included food and agriculture on a higher profile platform. But we need global governments to acknowledge this and to act.

Negotiations will carry on for the coming weeks and months, with the next COP scheduled for November 2022 in Sharm El Sheikh, Egypt. So while some may say Glasgow was all ‘blah, blah, blah’, at least governments are talking, remaining engaged with groups of like minded countries pushing ahead faster than others.

But they also need to bring a greater variety of people to the table, including groups representing peoples such as indigenous Ecuadorians living in the rainforest and nomadic groups from the Sahel – places where climate change is not waiting for signatures or listening to fine speeches.