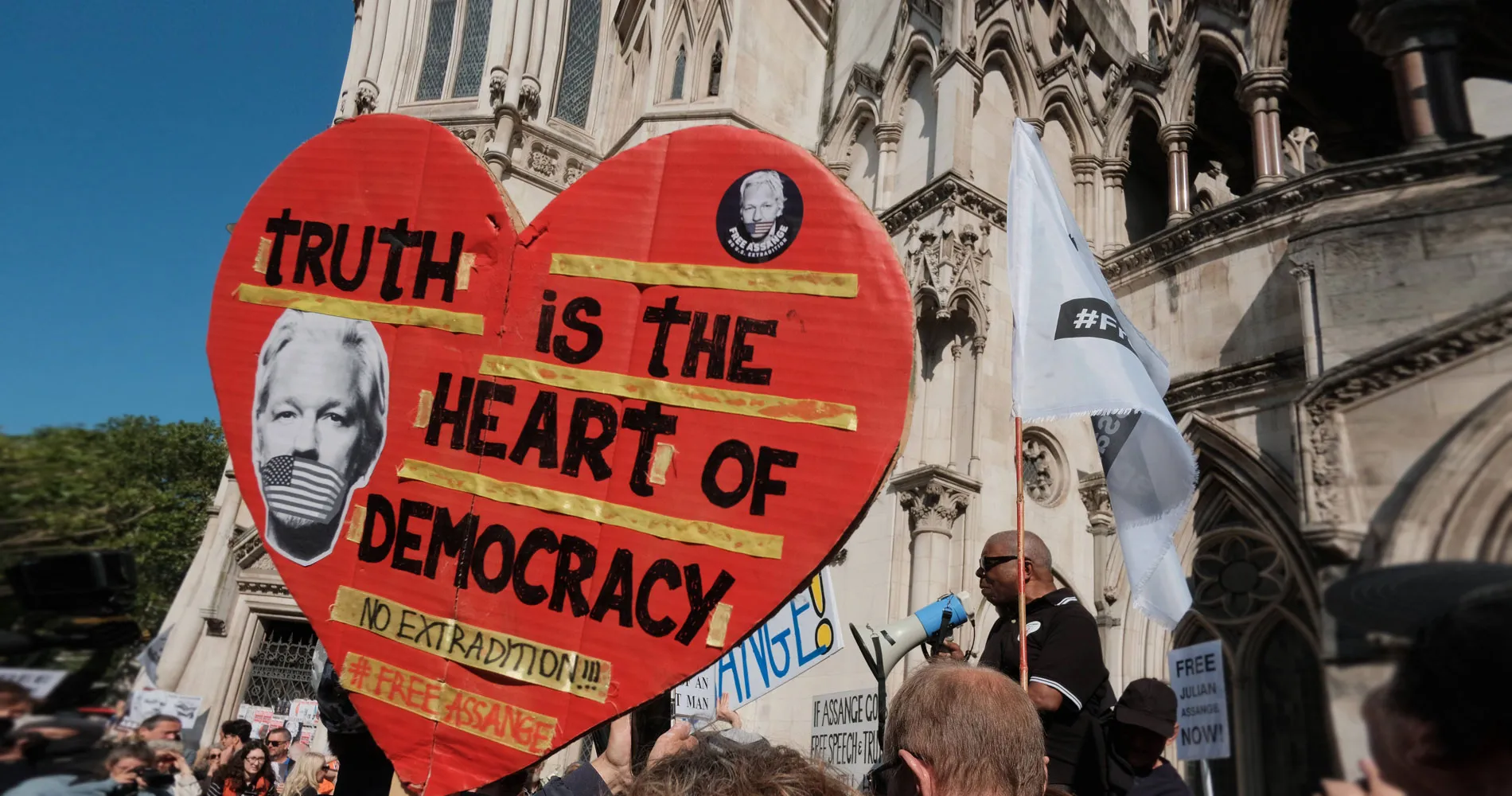

Julian Assange gains time to appeal against extradition to the US to face charges of leaking confidential military information which exposed US war crimes. But will this be sufficient to prevent potential prosecution, which could lead to 175 years in prison? What precedent is being set for journalists seeking to expose the crimes of governments and politicians?

David Deegan

27 May 2024

Arabic version | Chinese version | French version

Quis custodiet ipsos custodes? Juvenal’s question – who will guard the guardians? – is of vital concern for democracies. Journalists publishing in non-mainstream media outlets, commonly referred to as the fifth estate, are such guardians. They watch over the compliance with constitutional and other legal requirements of elected leaders and politicians and expose them if they act in contravention of their duties.

What is on trial in Julian Assange’s extradition battle is freedom of speech and democracy itself. If democratically elected governments cannot be held accountable for their criminal actions, there is no accountability and no rule of law. Democracies are built on these pillars and the separation of powers.

For many Julian Assange is one of the most recognized journalists of the century. In 2006, Australian-born Julian Assange launched WikiLeaks, an online platform for people to submit, with anonymity, a wide range of documents and videos that would shed new perspectives on official organizations and policies.

His platform WikiLeaks informed the world of the corruption in the family of former Kenyan president Daniel Arap Moi, exposed the standard operating procedures in the Guantánamo Bay detention centre and in April 2010 disclosed US war crimes in Baghdad by sharing a video of a US Apache helicopter attack in Baghdad in 2007, the Iraqi capital. The attack, which was not denied by the US government, killed a dozen people, including two Reuters journalists.

Later in 2010 the website released over 90 000 US military documents on the Afghanistan war, and close to 400 000 US files on the Iraq war.

In 2010 Assange sought refuge in the Ecuadorean embassy in London because the Swedish government was trying to extradite him to face charges of rape. Although all those charges were dropped in November 2019, earlier that year he had been forcibly removed from the embassy and detained in London’s high-security Belmarsh Prison. He has since remained in Belmarsh, where he continues to face the possibility of extradition to the US, having had 17 charges filed against him under the US Espionage Act of 1917. If convicted in the US he will face up to 175 years in prison.

In January 2021, a UK judge, Vanessa Baraitser, ruled that Assange should not be extradited to the US because he was likely to commit suicide in near total isolation. She stated: “I find that the mental condition of Mr. Assange is such that it would be oppressive to extradite him to the United States of America.”

Despite this ruling, and the fact that Assange has already spent 11 years in imprisonment, the US continues to seek extradition and press charges for WikiLeaks’ release of US military records, arguing that the leaks put the lives of US agents in danger.

The 1917 Espionage Act has been used by the US to prosecute spies and unauthorised leakers. Congress last modified it in 1950, but since then the act has not been significantly revised. In 1971 it was used to charge Daniel Ellsberg, an analyst for US Secretary of Defense, Robert McNamara. Ellsberg leaked a copy of McNamara’s report on the Vietnam War to the New York Times and the Washington Post. The report painted a picture of the US involvement in the war which was substantially different from what the government had previously been stated publicly. The charges against Ellsberg were subsequently dropped, and since then Democrats have criticized the Act saying that it is used to prosecute whistleblowers.

However, when the Justice Department referenced the Act in justifying a search warrant on President Trump’s Florida home, Mar-a-Lago, to obtain top-secret documents he had taken there, Republicans then denounced the Act.

The former UK Home Secretary Priti Patel approved Assange’s extradition order in April 2022. Assange’s supporters argued that he acted as a journalist to expose inappropriate US military action, and therefore should be protected under the press freedoms granted by the First Amendment to the US Constitution.

His supporters were not alone. The Australian federal parliament passed a resolution on 14 February 2024 supporting Assange’s 2010 Baghdad leak which had “revealed shocking evidence of misconduct by the USA” and underlining “the importance of the UK and USA bringing the matter to a close so that Mr Assange can return home to his family in Australia”.

On 19 February 2024 Amnesty International released a statement appealing to the US authorities to drop the charges, deeming the government’s pursuit of Assange a “full-scale assault on the right to freedom of expression”.

On 21 February 2024 Assange’s appeal against his extradition from the UK was concluded, but the two senior judges hearing the case, Victoria Sharp and Jeremy Johnson, did not issue the ruling until 20 May 2024, when they granted him permission to a full appeal within the UK. This ruling will enable Assange to challenge the US over whether, as an Australian citizen, his right to free speech would still be protected, and also to challenge how any potential trial would be conducted. He will continue to reside in Belmarsh Prison until the appeal is heard.

If Assange is ultimately extradited and prosecuted, it will bring questions on journalistic freedom into the spotlight. The Espionage Act has never before been used against the publishers of classified information. Daniel Ellsberg photocopied and leaked McNamara’s report, but it was other organizations which published extracts. Many newspapers, including the New York Times and the UK’s Guardian, published reports from WikiLeaks, but they are not on trial. Could that change in the future?

Daniel Ellsberg died on 16 June 2023. Coincidentally, less than a month later the UK National Securities Bill came into force. This bill does not contain a “Public Interest Defence” to protect journalists and whistleblowers.

Julian Assange has been imprisoned since 2010: nine years in the Ecuadorian Embassy and over five years in Belmarsh prison. If Assange’s latest appeal fails, and upon extradition to the US he is convicted, then those involved in investigative journalism anywhere in the world should rightfully fear for themselves and for the future of their profession. No longer will they be protected by freedom of expression and the rule of law. Ultimately, the future of democracy will be at risk if the United States government wins its extradition battle. No one anywhere will be safe and no one will guard the guardian.