Egypt is the most important bottleneck for global internet communication. Data travels across the ocean floor to Europe and beyond via underwater sea cables linking the Mediterranean and Red Sea. China, Russia and the US are now vying for predominance of these underwater intercontinental cables. Despite Google’s prestige subsea cable project “Blue Raman” linking India and Europe via Israel, Egypt’s pre-dominance of this underwater world remains undisputed. Today, the war in Ukraine and the Nord Stream explosions highlight the fragile nature of this vital undersea cable system.

Alexandra Dubsky, 16 June 2023

Almost 95 percent of intercontinental global internet traffic travels via undersea cables that run across the ocean ground. This plethora of cables, owned by both private and state-owned entities, transmits everything from consumer shopping data to government documents to scientific research conducted online.

When Russia annexed Crimea in 2014, the Russian military targeted the undersea cables linking the peninsula and the mainland to gain control of the information it carried. In 2019, Taiwan claimed that Beijing was using its Pacific undersea cables to spy and steal data. Closer to home, the US halted a Google project to build an internet cable from the US to Hong Kong, arguing that China might use its new national security law to gain access to cable data on the Hong Kong side. Today’s undersea cables transmit internet traffic all over the world and hold incredible amounts of data which translates into an enormous potential information pool for governments.

China and Russia are reshaping the internet’s physical design through companies that control internet infrastructure. Their goal is to route data more favorably and gain more control of internet bottlenecks which would be an advantage for spying. The exponential growth of cloud computing further increased the volume and the sensitivity of data travelling along these cables.

Those internet transfer cables have been built for the last 180 years by US private sector firms. In recent years large internet companies such as Facebook and Google have gained significant ownership of these cables, but also Chinese state-owned firms such as Huawei, China Telecom and China Unicom have gained control of a large chunk of these cables.

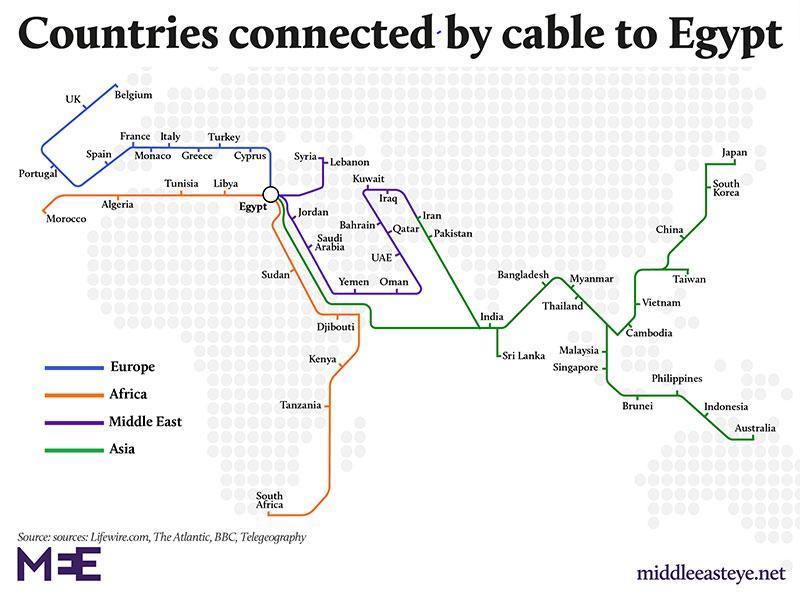

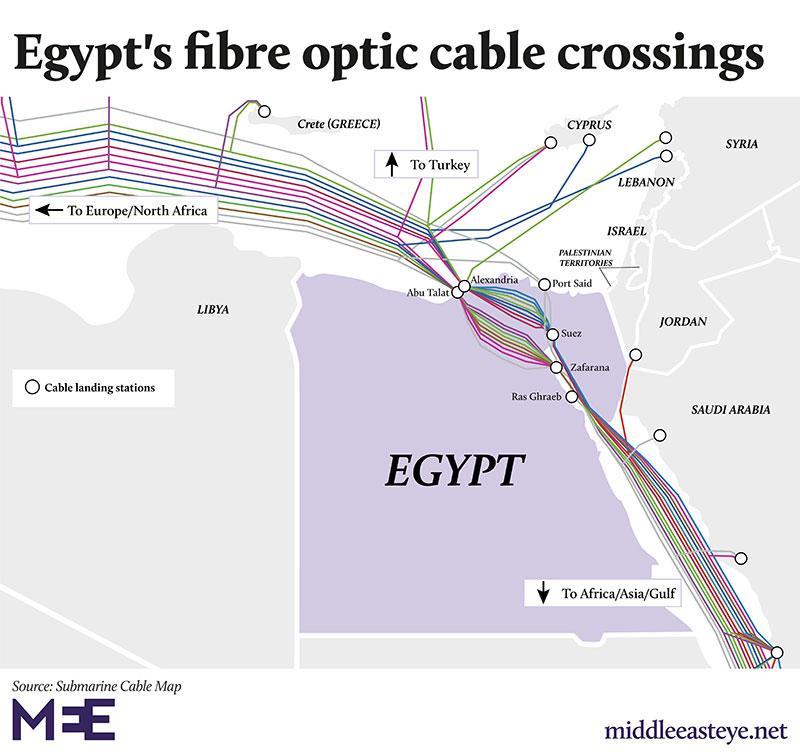

The Asia Africa Europe 1 internet cable runs c. 25000 km along the seafloor, linking Hong Kong to Marseille. A total of 16 of these submarine cables stretch along c. 1932 km through the Red Sea before they pass Egypt on land and continue to the Mediterranean Sea, connecting Europe to Asia, a route that also includes the famous chokepoint of the Suez Canal.

In a June 2021 report by the European Parliament on “Security threats to undersea communications cables and infrastructure – consequences for the EU”, determined that “the most vital bottleneck for the EU concerns the passage between the Indian Ocean and the Mediterranean via the Red Sea because the core connectivity to Asia runs via this route,” naming extremism and maritime terrorism as the main risks.

There are 10 cable landing stations on Egypt’s Mediterranean and Red Sea coastlines and there are at least 15 terrestrial crossing routes across the country. Ten of these cable landing stations are operated by the Egyptian telecom giant Telecom Egypt (TE). Its cables span a region from the Mediterranean to as far as Singapore.

According to TE 17 percent of internet traffic streams through Egypt. Other sources have indicated that this estimate is too conservative and estimated the percentile of global internet traffic through Egypt to be as high as 30 percent: effectively digitally linking a whooping 1.3 billion to 2.3 billion people around the world.

“It is one of Egypt’s trump cards, like the Pyramids, which never goes out of fashion. They [Egypt] are used to making business out of transit and tourism, but now they’re doing it with data. It is a digital Suez Canal, which trades on its geopolitical position,” according to Hugh Miles, founder of the Egyptian podcast “Arab Digest”.

There is a fee that’s charged for capacity, but it is not the price that worries the industry. The challenge is if there is a leak, or some kind of regulatory uncertainty, that blocks the transfer.

Interruptions have certainly happened in the area, partly due to the relatively shallow level of water of the Red Sea, causing several cable cuts throughout the years. The Egyptian navy arrested three people who were caught cutting internet cables in the shallow waters of the Red Sea in 2013. Other nearby cables also faced disruptions at the same time.

Egypt is however the only feasible existing route. Connections that move around Africa are longer, and to the North there are no reasonable alternatives. Every other route goes through even more troubled places such as Russia, Syria, Iraq, Iran or Afghanistan.

Elon Musk’s Starlink promotes satellite internet, it cannot replace physical infrastructure completely. There is no viable replacement for underwater cables.

The biggest challenge to Egypt’s sea cable monopoly comes from Google. The company announced in July 2021 that it was building the “Blue Raman” subsea cable that would link up India and Europe. The cable will run through the Red Sea, but will not cross land in Egypt to reach the Mediterranean but go over Israel. The new venture, which according to Google will be ready for service in 2024, is expected to be followed by more cables that will eventually travel through the Jewish state. Other planned alternative routes include a connection between Africa, the Americas and Singapore.

Due to its geographic location Egypt will however always remain at the heart of Europe’s and Asia’s internet connections and connectivity. Alan Mauldin, Research Director at Telecommunications Research Firm Tele Geography in Washington DC: “If you want to route cables between Europe and the Middle East to India, where’s the easiest way to go? It is via Egypt, as there’s the least amount of land to cross.”

And from the looks of it, this is not going to change any time soon.