A hidden burial chamber has been recently uncovered in Egypt during cleaning operations at the 3 900-year-old Tomb of Djefaihapy. This discovery promises to unveil new perspectives on the Middle Kingdom of ancient Egypt, a time characterized by notable wealth, innovation, and artistry — despite the limited remnants we possess today.

Aly Mahmoud

11 November 2024

Chinese version | French version | German version | Spanish version

A joint archaeological excavation campaign led by Sohag University (Egypt) and the Institute of Egyptology of the Freie Universität (Germany). together with teams from Kanazawa University, Japan, and the Polish Academy of Sciences, announced on 2 October 2024 the discovery of the burial chamber of Edi, the daughter of the governor of Assiut during the reign of King “Senusret I.”

This collaboration, established 20 years ago, led by Prof. Dr. Jochem Kahl of the Reie Universitat Berlin, resulted in the discovery of previously unexplored burial shafts, some of which are architecturally unique and include a 28-meter-deep shaft, which was only fully excavated after six seasons. One of these burial sites, Tomb I, belongs to the provincial governor Djefaihapi I (approx. 1900 BC) and is considered the largest tomb on Gebel Asyut Al Gharbi.

Edi’s hidden burial chamber © Egyptian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities

Edi’s hidden burial chamber © Egyptian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities

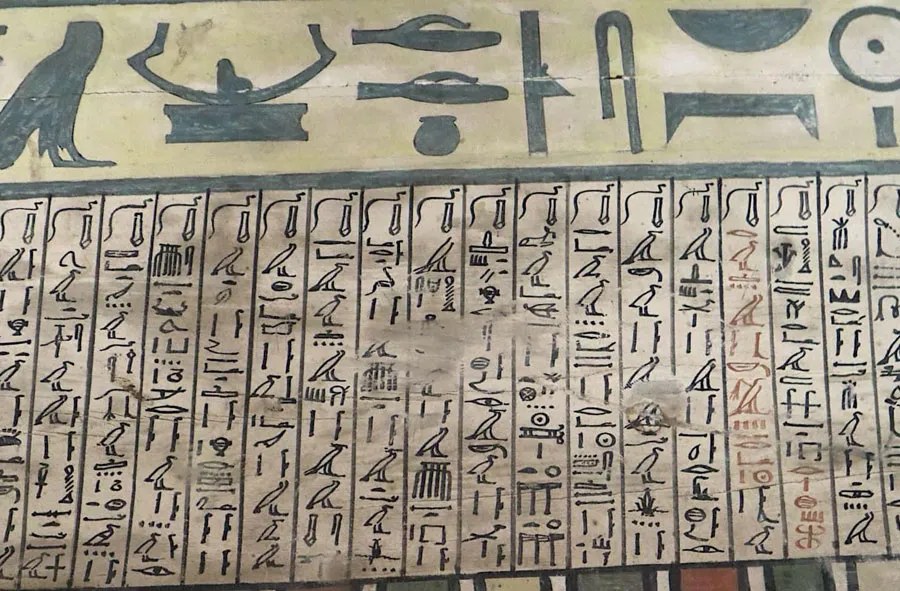

Inscriptions of funerary texts depicting the ancient Egyptian journey to the afterlife © Egyptian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities

Inscriptions of funerary texts depicting the ancient Egyptian journey to the afterlife © Egyptian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities

Edi’s wooden coffin © Egyptian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities

Edi’s wooden coffin © Egyptian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities

Djefaihapi (also ‘Difai—Hapi’) governed the region of Assiut from around 1961 BC to 1915 BC. His burial site, Tomb 1, is recognized as the largest preserved non-royal rock-cut tomb in the ancient Egyptian Middle Kingdom. It is around 120 meters long and has a ceiling of more than 11 meters high. This region was well-known for its thriving trade routes, wealth in minerals and gold, and proximity to Nubia.

Most recently, during an excavation campaign that initially aimed to clean the shaft of Djefaihapi’s tomb, the excavation team unexpectedly discovered the long-concealed burial chamber of the noblewoman Edi, who was the only daughter of Djefaihapi. This discovery will help understand the ancient Egyptian Middle Kingdom, a period often overshadowed by the earlier Old Kingdom, known for the pyramids, and the later New Kingdom, renowned for King Tutankhamun.

Edi’s burial chamber was located in a side chamber closed off by rubble stones in a vertical shaft. According to Dr. Mohamed Ismail Khaled, Secretary-General of the Egyptian Supreme Council of Antiquities, the chamber was found 15 meters deep in the northern shaft of her father’s tomb.

In the chamber, archaeologists found two intricately nested wooden coffins. One coffin was placed inside the other and both were adorned with inscriptions of funerary texts depicting the ancient Egyptian journey to the afterlife. The outer coffin’s length is 2.6 meters, while the inner coffin is 2.03 meters long. The Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities described them as among the “most magnificent” ever found from the Middle Kingdom.

Wooden statue found inside Edi’s burial chamber © Egyptian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities

Wooden statue found inside Edi’s burial chamber © Egyptian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities

Wooden statue found inside Edi’s burial chamber © Egyptian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities

Wooden statue found inside Edi’s burial chamber © Egyptian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities

The team found evidence of previous looters impacting the site, removing Edi’s remains from the coffins and destroying the canopic jars that held her internal organs. Luckily, after excavation, the campaign rescued some artifacts, including the lid of one of the coffins, fragments of some of the canopic jars, and some of Edi’s skeletal remains.

These canopic jars were key objects of ancient Egyptian burial practices and were designed to hold the extracted embalmed internal organs, which were removed during the mummification process. They were usually made of pottery, glass, or faience. Certain organs such as intestines, liver, lungs, and stomach were placed in separate jars shaped in the form of the heads of the four sons of the god Horus for protection. The heart was left inside the body as they believed it was the seat of a person’s soul.

These canopic jars and the preserved body have been examined by experts to uncover details about the person’s life and age at the time of death. After an initial analysis of Edi’s remains, Dr. Mohamed Ismail Khaled, Secretary-General of the Egyptian Supreme Council of Antiquities, suggests that Edi might have had a congenital foot defect, and she likely died at a young age, possibly before the age of 40.

Following this discovery, the Egyptian Minister of Tourism and Antiquities, Sherief Fathy, expressed his gratitude to the joint excavation campaign for uncovering more secrets of the history of ancient Egypt and declared that the ministry is ready to fully facilitate and support similar excavation campaigns to ensure the completion of their work in the best possible way.

The excavation team also announced that they will continue studying the rescued artifacts of Edi and her father to gain a deeper understanding of the Middle Kingdom, including the position of women in ancient Egypt.