From their childhoods in Palermo to their work in the historic Maxi Trial, Falcone and Borsellino dedicated their lives to battling organized crime. They were heroes fighting for justice against an all-powerful enemy, the Sicilian Mafia. What drove them along this path? What legacy have they left?

Yegor Shestunov

26 June 2024

German version

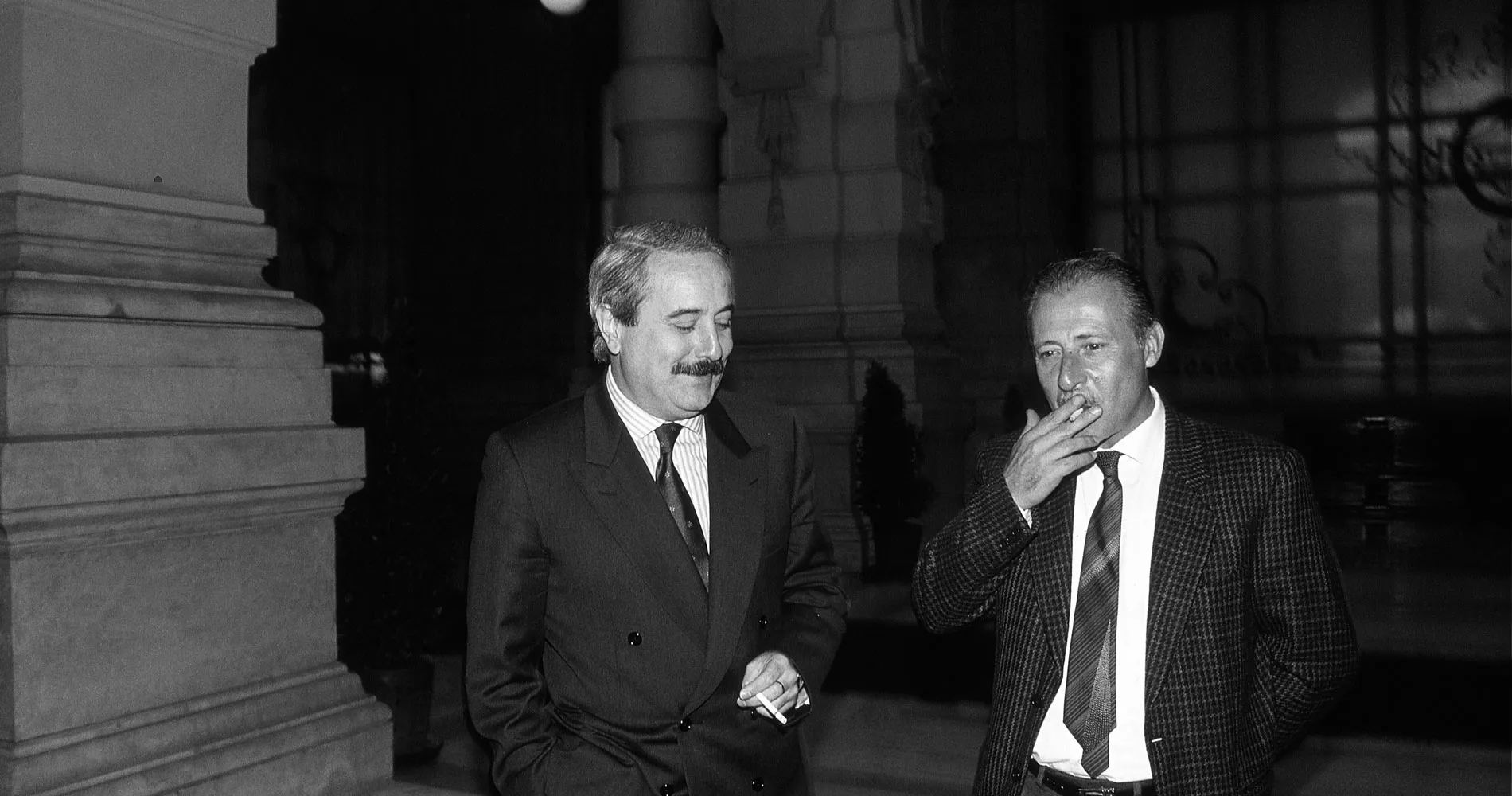

Giovanni Falcone, his wife, and three police officers were assassinated 32 years ago by a bomb near Palermo, Italy. Paolo Borsellino was assassinated 57 days later.

Who were Giovanni Falcone and Paolo Borsellino? Why, in 2006, did Time magazine name them heroes of the last 60 years? Why are airports, schools and other public buildings named after them? What inspired the movies depicting their lives, like the 1999 television movie “Excellent Cadavers” and “The Angels of Borsellino”? And why is there a monument at the FBI’s National Academy in Virginia in honour of Falcone?

Giovanni Falcone and Paolo Borsellino both grew up in middle-class families in Palermo’s La Kalsa district, played soccer together and witnessed organized crime, violence, and death from an early age. They saw their classmates join the Mafia, becoming smugglers and killers, like Tommaso Spadaro, a boy with whom they once played ping-pong, who later in life became one of Sicily’s Mafia bosses.

From a young age, Falcone had a strong sense of justice. At school Falcone would occasionally get into fights with larger children, if he felt they mistreated his friends. After school, Falcone, like Borsellino, studied law at Palermo University. Both decided to join the judiciary but, as noted by the Falcone Foundation, neither initially thought they would become involved in the fight against the Mafia. Falcone was appointed a judge and gravitated towards penal law after serving as a district magistrate, while Borsellino, after passing the judiciary exam, worked in many Sicilian cities as a magistrate.

However, for anyone committed to upholding the law, the Mafia’s pervasive influence would have been impossible to ignore, but attempts to investigate and combat Sicilian Mafia often resulted in deadly reprisals. In September 1979, Falcone joined the “Office of Instruction,” the investigative branch of the Prosecution Office of Palermo, shortly after the assassination of Judge Cesare Terranova, a former parliamentary deputy and anti-Mafia reformer. Borsellino’s close co-investigator, Carabiniere Captain Emanuele Basile, was shot in 1980. The Examining Officer at the Palermo Court, Rocco Chinnici, who worked with Falcone and Borsellino to study the Mafia’s links to political and economic powers in Sicily and Italy, was killed by a car bomb in 1983. Bodyguards, police officers, and bystanders also perished in these attacks.

The Mafia’s political and social connections, corrupt politicians and networks of informers and criminal organizations were almost always one step ahead of Palermo’s Antimafia Pool, created by Judge Rocco Chinnici in the early 1980s. (The Antimafia Pool was a group of investigating magistrates in Palermo’s Prosecuting Office. They shared information and developed new investigative and prosecutorial strategies in their fight against the Sicilian Mafia.)

Fighting the Mafia came with a huge risk. Even with sufficient evidence, convictions were rare, and most Mafia bosses and members walked free from prison sentences. That was before investigations by Falcone, Borsellino, Chinnici and another magistrate, Antonino Caponnetto. Their efforts led to the historic Maxi Trial, a six-year court hearing from 1986 to 1992, during which Sicilian prosecutors indicted 475 Mafiosi for various crimes. Most were convicted, and 19 bosses received life sentences.

This success provoked a judiciary revolution in Italy. With 475 initial defendants and around 200 defense lawyers, the Maxi Trial is considered one of the largest trials against organized crime groups ever held in world history, and certainly the most significant trial ever against the Sicilian Mafia. It was held inside the walls of Ucciardone prison, in a bunker-style courthouse that had been constructed specifically for this purpose. During the trial, and afterwards, several judges and magistrates were killed by the Mafia, including Falcone and Borsellino, who played pivotal roles in bringing convictions.

The most crucial evidence came from Tommaso Buscetta. During the Great Mafia War, from 1981 to 1984, also referred to as the Mattanza (The Slaughter in Italian), the Mafia was redistributing power within the organization. There was violence within Mafia structures themselves, as well as violence against the state, prosecutors, judges, detectives, politicians, and activists. After Buscetta’s two sons disappeared without a trace, he agreed to reveal what he knew about the Mafia to Falcone.

For 45 days, he explained to Falcone the inner workings of the Sicilian Mafia known as Cosa Nostra, including the Sicilian Mafia Commission which decided on the course of actions and dispute settlements within Cosa Nostra. For the first time, the strict code of silence within the Mafia was broken, and investigators could confirm the existence of the Cosa Nostra and its hierarchical structures. Buscetta, however, refused to speak to Falcone about the political ties of Cosa Nostra. In Buscetta’s opinion, Italy was not ready for statements of that magnitude.

In 1991, while the trial was in progress, Falcone accepted a post in the Ministry of Justice in Rome, and he began planning the restructuring of the Italian prosecution system. He aimed to counteract the decisions of Supreme Court Judge Corrado Carnevale, known as the “sentence-killer,” who was allowing many defendants from the Maxi Trial and other Mafia cases to escape prison.

This was the turning point. On 23 May 1992 Falcone, his wife Francesca Morvillo, and three police officers were killed near Capaci, just outside Palermo, by a hidden bomb planted beneath a motorway. Weeks later, Borsellino was killed along with five police officers by a car bomb at the entrance to his mother’s apartment.

Later that same year, posters displaying solidarity with Giovanni Falcone and Paolo Borsellino proclaimed: “You did not kill them: their ideas walk on our legs.” Because of them, for the first time, it was proven that the Mafia in Sicily existed. It was because of their endeavours, which ended so tragically, that a massive crackdown on the Mafia began and more than 200 of some of the most dangerous men in Italy were sentenced, totalling more than 5000 years.

The Maxi Trial did not eradicate the Italian Mafia, but it showed Italy and the world that such trials were possible. The courage of Falcone was honored posthumously by Train Foundation’s Civil Courage Prize and many public institutions were named after Borsellino and Falcone, including the Falcone-Borsellino Airport in Palermo.