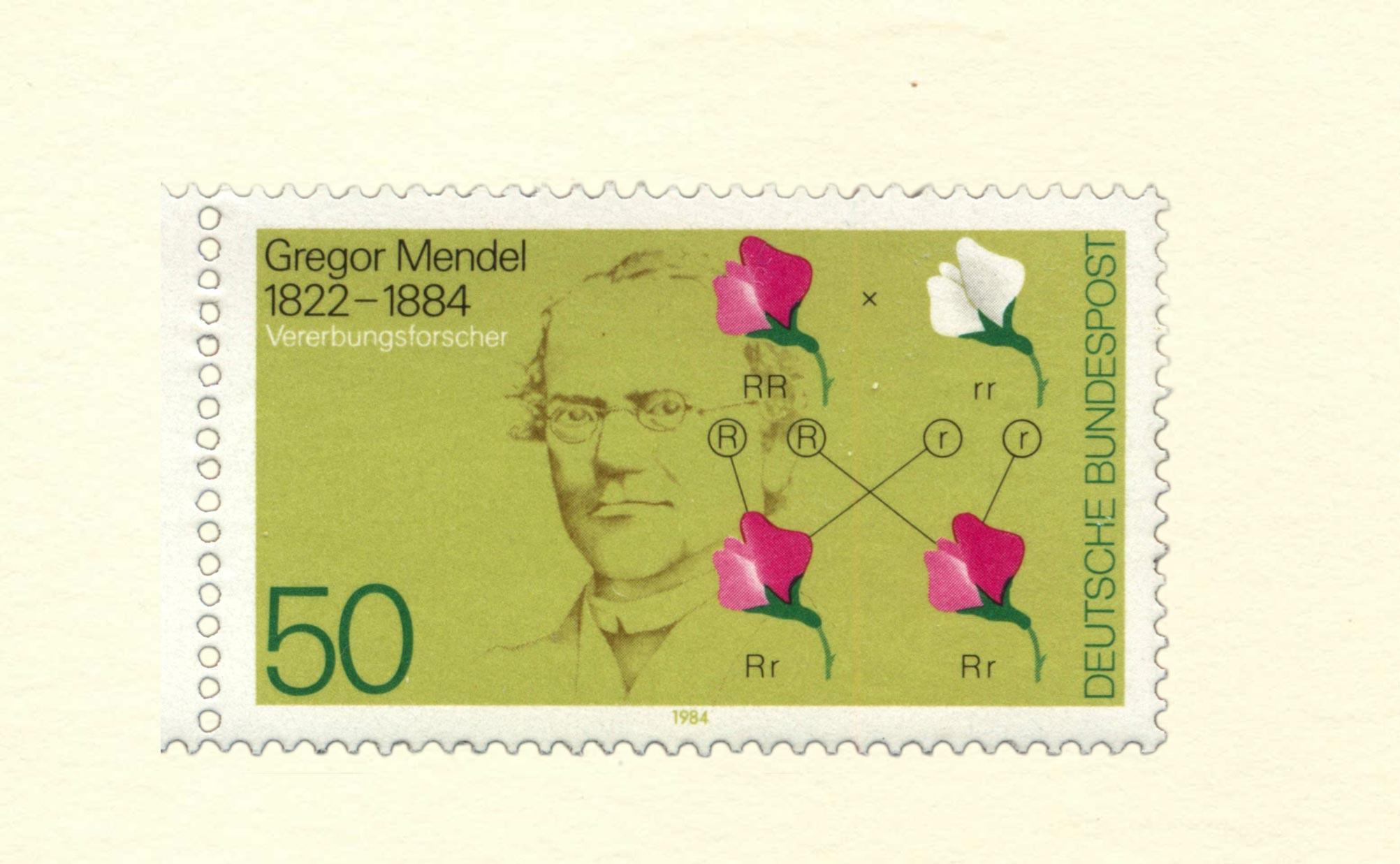

This year marks the 200 anniversary of Gregor Mendel who was born on 20 July 1822. Misunderstood during his lifetime, he is today considered the founder of the modern science of genetics. Celebrations, symposia, exhibitions and lectures are taking place around the globe to celebrate this unique brilliant individual – who was also a catholic priest and an abbot.

Yegor Shestunov, 12 September 2022

“About 13.5 billion years ago, matter, energy, time and space came into being in what is known as the Big Bang. The story of these fundamental features of our universe is called physics).About 300,000 years after their appearance, matter and energy started to coalesce into complex structures, called atoms, which then combined into molecules. The story of atoms, molecules and their interactions is called chemistry. About 3.8. billion years ago, on a planet called Earth, certain molecules combined to form particularly large and intricate structures called organisms. The story of organisms is called biology. About 70,000 years ago, organisms belonging to the species Homo sapiens started to form even more elaborate structures called cultures. The subsequent development of these human cultures is called history” (Yuval Noah Harari, Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind)

The chances of life appearing on Earth are slim. The chances of conscious life appearing on a planet are slimmer. The chances of conscious life thriving, contemplating, and continuing long enough for it to start asking existential questions and start studying itself are even slimmer.

In a forever-changing world, particularly in an even faster forever-changing human world, discoveries, as well as predictions, are not easy to make. Some human inventions, ideas and creations age well: they become pillars of the society, or community dogmas, or fundamentals of certain sciences and art. Others are discarded forever, and rarely rediscovered. Of particular fascination are the ideas ahead of their time, requiring the most observant and cautious thinkers, the most brilliant and sophisticated minds to discover what was as yet unknown.

Gregor Mendel was an Austrian biologist, meteorologist, mathematician as well as a teacher, beekeeper; Augustinian monk, Catholic priest and abbot. This year is the 200th anniversary of his birth in Silesia, which was part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Gregor Mendel is commonly referred to as the founder of the modern science of genetics.

According to various outlines of his sermons which are still preserved, he was once a man with broad shoulders and a stout figure. He was enthusiastic and passionate about his faith, very communicative with an excellent sense of humour. One of his fellow monks spoke of him as “affibilis unicuique” – kind and friendly to everyone.

“By his generosity, kindness and mild‐manners, Mendel acquired universal respect and sympathy. He left no appeal for help unanswered and, in an amicable manner, he knew how to dispense help without letting the petitioner feel the charity.” (According to Father Clemens Richter, Mendel’s great-great-grandnephew, the quote comes from one of Mendel’s obituaries)

Between 1856 and 1863 Mendel conducted a series of observations, during which he cultivated around 30 000 plants. These observations later became fundamental to the rules of heredity – the passing of traits from parents to offspring. He studied the plant height, the shapes and colours of pods, seeds, and flowers and concluded his experiments demonstrated role of the “invisible factors” – what we commonly refer to nowadays as genes. Mendel did not possess knowledge about chromosomes, so he simply called genes “unit factors”. In particular, he described the four laws of inheritance: the law of segregation, law of dominance, law of independent assortment, and law of unit characters. Of a particular fascination is that Mendel cultivated, observed, studied, and experimented on plants in his monastery garden.

The law of segregation, or the first law of inheritance, states that maternal and paternal alleles (allele is a specific form of a gene with two or more versions of a DNA sequence) segregate themselves into separate daughter cells; that two copies of each genetic factor segregate during development of gametes (a gamete is a reproductive cell of plant or animal), ensuring each offspring attains one genetic factor.

The law of dominance, or the second law of inheritance, states that should parents with pure and contrasting traits produce offspring, only one form of a trait appears in the next generation, exhibiting the dominant trait in the phenotype.

The law of independent assortment states that the alleles of two or more different genes are sorted into gametes independently of each other, meaning that the allele a gamete receives for one particular gene does not influence the allele received for another gene.

The law of unit character states that the unit factors (the genes) exist in two sets, or in two pairs, and from each parent one set is inherited – meaning that every trait has two unit factors, in pairs, which control it.

As is often the case with those who are ahead of their time, Mendel, according to Father Clemens Richter, felt misunderstood as many of his fellow monks discouraged him from proceeding with his work. He suffered from a fight with the Austrian government over the exorbitant taxation of his abbey.

As with other path-breaking ideas, the initial reception of Mendel’s work was rather weak. It was ignored and criticized by the scientific community. When he died, very few were aware of how pivotal his work was. This awareness came only 30 years later when Erich von Tschermak, Hugo de Vries and Carl Correns verified and confirmed Mendel’s findings.

“A few months before his death he told a novice in the monastery, Franz Barina who later became his successor as abbot: “Even though I have experienced some dark hours during my lifetime, I am grateful that the beautiful hours have outweighed the dark ones by far. My scientific work has brought me great joy and satisfaction; and I am convinced that it won’t take long before the entire world will appreciate the results and meaning of my work.” To a friend he expressed his firm opinion: “Meine Zeit wird kommen” (my time will come).” (Father Clemens Richter, Mendel’s great-great-grandnephew)

He was right. He knew.