Max Weiler is one of the most important Austrian painters of the 20th century. His painting was deeply influenced by the painters of the Sung dynasty (960–1279). It is no coincidence that Max Weiler’s late work was honored in 1998 in a large retrospective at The National Art Museum of China (NAMOC) in Beijing, the first Austrian living artist to be so honored.

Sophie Cieselar, 7 April 2022

Max Weiler (1910-2001) is undeniably one of the most important Austrian painters of the 20th century. His work, honored in numerous exhibitions and publications, often met with incomprehension during his lifetime. In many cases, his works were too progressive, too much ahead of his time. It was not until his advanced age that he received widespread recognition. His art seems to have developed independently of all the currents surrounding him and is not easily categorized. But, like many artists of the first half of the 20th century, he was also concerned with the central question of what art can and should be. In this way, he repeatedly came into contact with the international movements of his time.

His work is characterized by constant new beginnings. Max Weiler never rested on what he had already achieved – but always seemed to be questioning everything. In his diaries, the Tag- und Nachtheften (The Day and Night Notbook), one encounters Max Weiler as a seeker, as a doubter, and as a man deeply attached to nature.

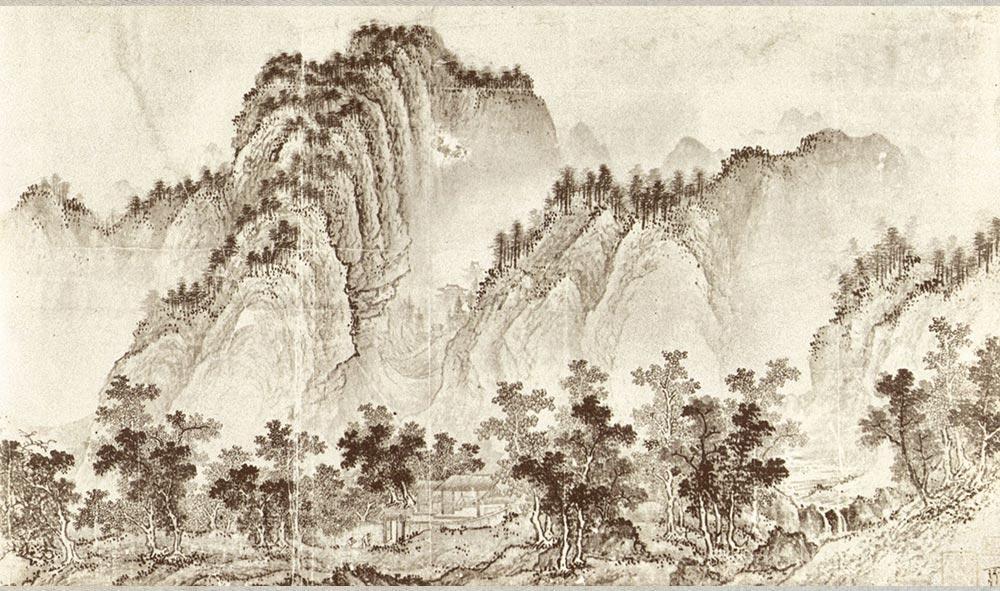

Master of the Sung Dynasty, A clear day in the valley, 12th century, h 57.9 cm, ink on paper (Museum of Fine Arts, Department of Prints, Drawings and Photographs, Boston).

© Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

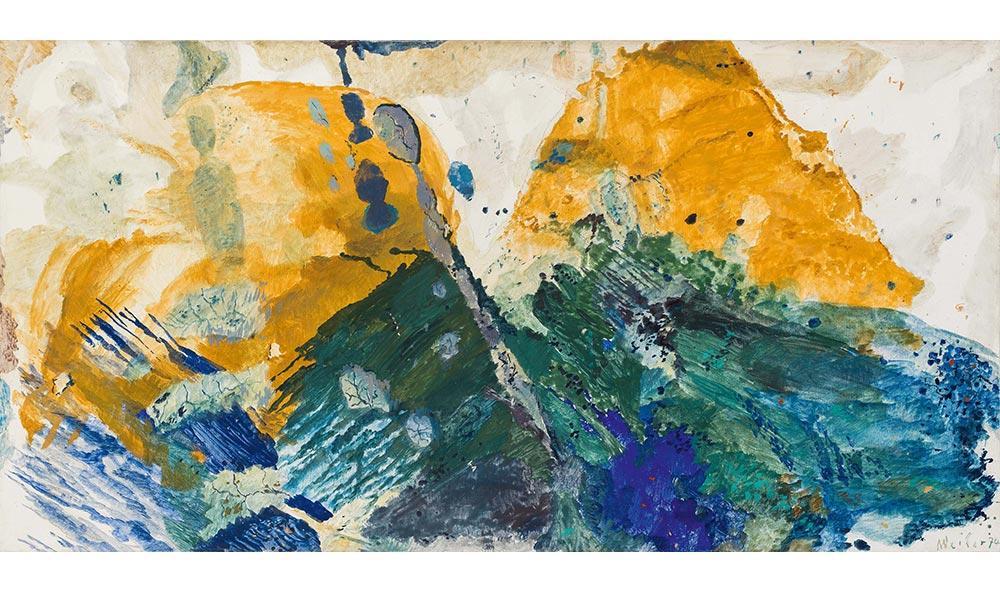

Max Weiler, 2 Ochre Mountains, 1974, egg tempera on canvas, 100 x 195 cm

© Galerie Kovacek & Zetter, Vienna

“I cannot say exactly what it is that I do. Rather, I can paraphrase it as images corresponding to all that exists, and images that look into the infinite in nature…” (Max Weiler, Salzburg 1986, quoted in: Otto Breicha, Weiler. Die innere Figur, Salzburg 1989, p. 285).

His concept of nature goes far beyond painting still lifes and landscapes. Nature is merely the starting point for his inspiration and his deeply internalized passion for the creation that surrounds us. From this he develops his own representation of nature in his painting. “My work is a spiritual one” (Max Weiler, Tag- und Nachthefte, 1972) he says, referring to finding his motifs in his deepest inner self.

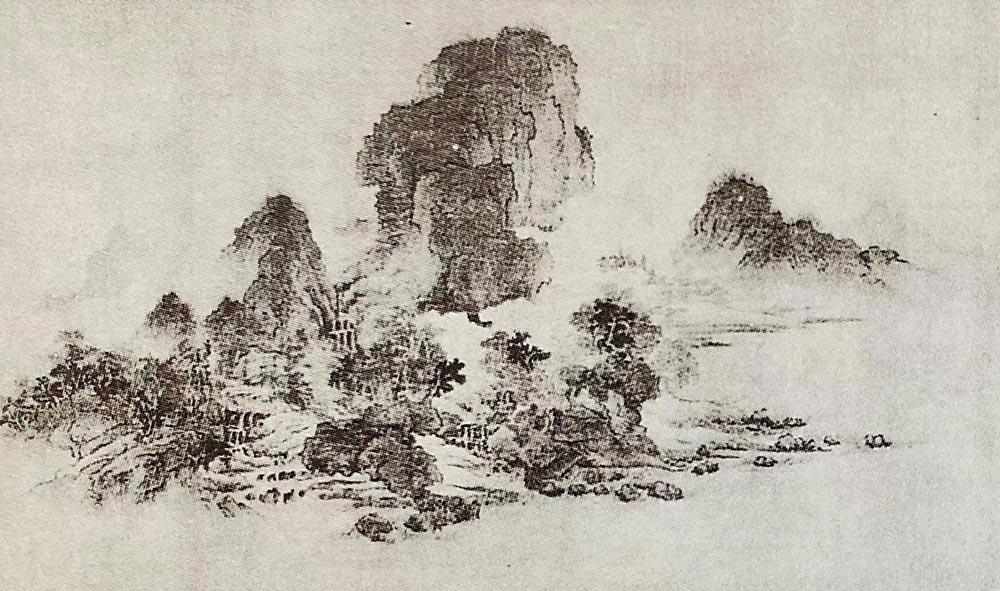

The influence of Karl Sterrer, Weiler’s professor at the Academy of Fine Arts, on the young artist’s creative work and spiritual development cannot be underestimated. For Weiler’s further work, it was decisive that Karl Sterrer introduced him to Chinese Sung painting. The affinity Weiler experienced with the early Asian landscape painting was formative for his further work. He recognized that the Chinese painters of that period were not concerned with the exact replication of a landscape but rather with the mood and atmosphere awakened in the viewer. It is not the exact reproduction of an object that was desired, although mountains, rivers, trees and clouds could be recognized. Rather, it was the capturing of the essence of a landscape, its inherent movements and patterns of development.

Wang Shen, 2nd half 11th century, Rivers and mountains in the fog (detail), ink on silk.

Wang Shen, 2nd half 11th century, Rivers and mountains in the fog (detail), ink on silk.

© Shanghai Museum, Shanghai, China

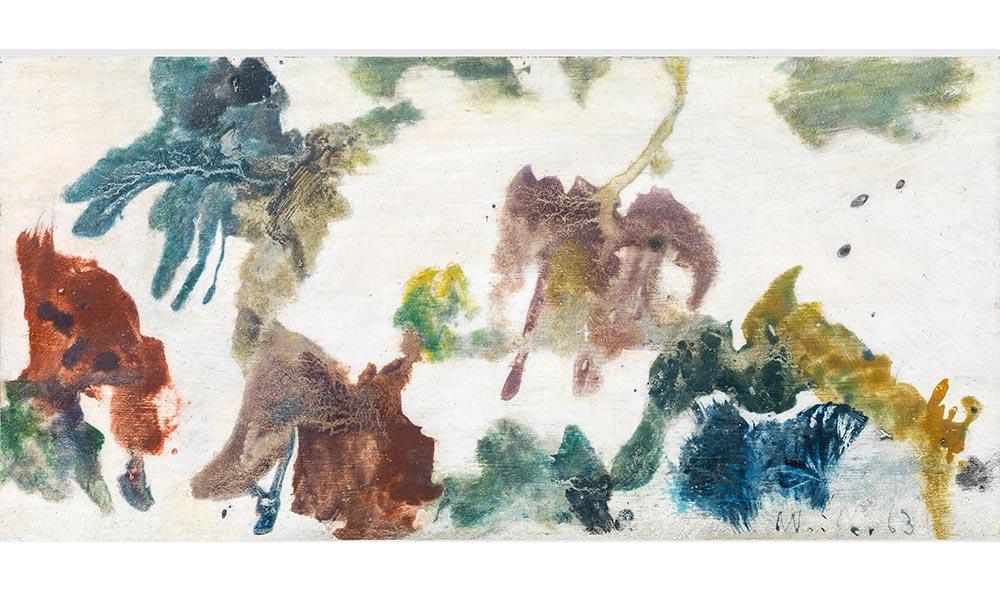

Max Weiler, Like a Landscape, 1963, egg tempera on hardboard, 21.7 x 45.2 cm

Max Weiler, Like a Landscape, 1963, egg tempera on hardboard, 21.7 x 45.2 cm

© Galerie Kovacek & Zetter, Vienna

Each work should have a chi, which means “life,” “life of its own,” or “energy.” Only in this way can one approach the highest reality and truth and this became Max Weiler’s artistic aim in life: the striving for the highest level of spirituality and grasping through his art the essence of nature. Weiler was also fascinated by the technical approach of the Sung painters, by the way the Chinese ink painters achieved sharpness and contour solely through the skillful combination of dry and wet painting techniques. In his work, too, there is a masterful liquification of colors and forms.

To ensure technical realization, Max Weiler abandoned oil painting around 1950 and from then on used only tempera paints, which allowed a more fluid, transparent application of color and a more direct visual language. This was also about creating tensions that result from the contrast between abstraction and the still recognizable figurative representation. All this served to make visible processes and relationships of forces found in nature: everything is in flux, there is a constant mobility in the sense of becoming and passing away.

Max Weiler does not paint nature, but is concerned with the “re-creation of nature without any resemblance to nature… I make the atmosphere, the moods, trees, grasses and things of nature with my own forms” (Max Weiler, Tag- und Nachthefte, 1972). He discovered that the ability of transformation does not lie just anywhere but precisely in the colors chosen and, in the forms created. They are themselves, in their unstable, watery or liquid nature, the very substance of metamorphosis.

This is also the artistic medium used by the painters of the Sung dynasty, “nature can intertwine with spirituality” (Boehm, p. 189). The path to abstraction is thus to be understood in the sense that Max Weiler transforms the essence of nature into his own artistic language, on which he subsequently builds. Seen in this light, his “work has nothing to do with religion, but with creation” (Max Weiler, Salzburg 1986, text published by the Rupertinum, in: Otto Breicha, Weiler. Die innere Figur, Salzburg 1989, p. 285).

It is no coincidence that Max Weiler’s late work was honored in 1998 in a large retrospective at The National Art Museum of China (NAMOC) in Beijing, the first Austrian living artist to be so honored.