The decision of Zimbabwe and Namibia to slaughter almost 1000 wild elephants, hippos and zebras citing climate change and their starving human population has been strongly criticized by the international community. Human populations in both nations have exploded in the past decades and are expected to continue their exponential growth. Blaming climate change is a weak excuse, when in fact it was humans who were responsible for mismanagement of resources and ineffective government policies.

Silvia Caschera

31 March 2025

Arabic version | Chinese version | French version | German version

Zimbabwe’s population has doubled in the past 40 years and is expected to increase an additional 58% by 2030. Namibia’s population has doubled in the past 35 years. In the next 30 years its population is predicted to increase another 50%. Both Namibia and Zimbabwe live heavily from tourism. Tourism makes up 12% of Namibia’s GDP and in Zimbabwe, the tourism industry has an annual growth rate of 35%. Wild animals play a major part in this industry.

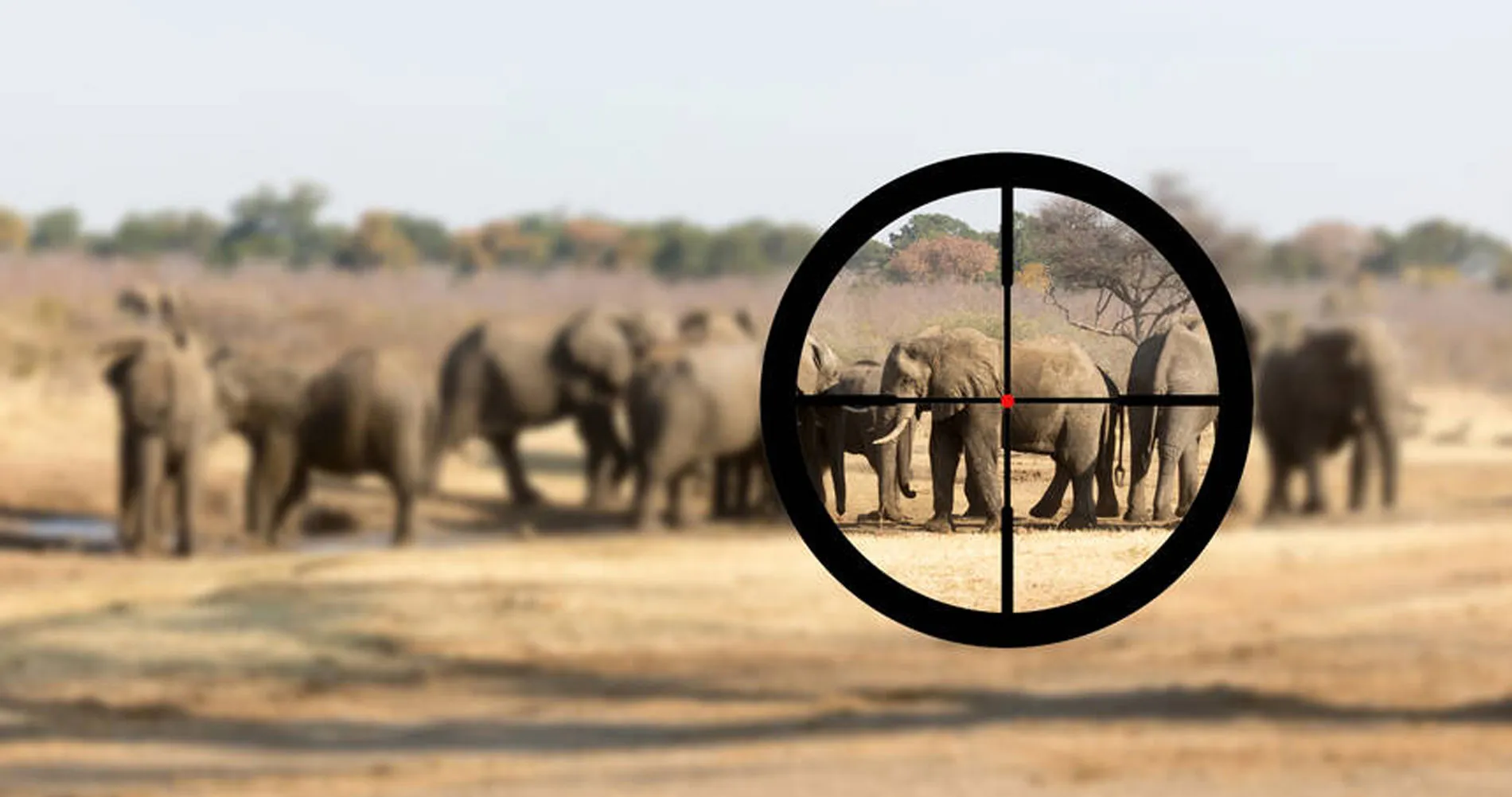

The decision by Namibia in mid-August 2024 to cull 723 wild animals, such as elephants, zebras, and hippos, citing the worst drought the country has experienced in decades, is a reminder how the competition between human and wildlife populations for finite resources is coming to a head. The government claims that this action is essential to decrease grazing pressures, enhance water availability, and supply game meat to local communities suffering from severe food insecurity.

In mid-September 2024, Zimbabwe made a similar decision to slaughter 200 elephants to feed its citizens left hungry by the drought.

This practice has ignited a contentious discussion regarding its ethical implications and necessity. One of the primary ethical issues with culling is the welfare of the animals involved. Animal rights organizations, such as People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA), argue that culling is inherently cruel and causes unnecessary suffering. The process of capturing and killing animals can be traumatic and painful, raising questions about the humanity of such practices.

Farai Maguwu, who leads the Zimbabwe-based advocacy group the Center for Natural Resource Governance, posted on X: „Culling of elephants must be stopped,” adding that “Elephants have a right to exist,” so that “future generations have a right to see elephants in their natural habitat.”

Critics of culling also emphasize the intrinsic value of wildlife. They argue that animals have a right to exist without human interference and that killing them for human benefit is morally wrong and economically illogical, considering the dependence of these African countries on tourism. This perspective challenges the notion that human needs should always take precedence over the lives of other species.

There are also concerns about the long-term ethical implications of relying on culling as a solution. If culling becomes a common practice, it may set a dangerous precedent, leading to the normalization of killing wildlife to address human problems. This could undermine conservation efforts and erode the ethical standards of wildlife management.

Culling can have profound ecological impacts by disrupting natural ecosystems. Removing a significant number of animals from an ecosystem can lead to imbalances, affecting other species and the overall health of the environment. For example, elephants play a crucial role in their ecosystems by aiding in seed dispersal and landscape maintenance. Culling elephants and other wild animals can disrupt these processes, leading to unforeseen consequences for biodiversity.

The removal of certain species through culling can also affect population dynamics. In some cases, culling may lead to an increase in the population of other species, creating new ecological challenges. For instance, culling and hunting predators can result in an overpopulation of prey species, which can then lead to overgrazing and habitat degradation. Both Zimbabwe and Namibia are a major destination for trophy and big game hunting. Lions and other predators are highly sought after hunting trophies. Killing predators leads to a population increase of prey species.

Another ecological concern is the potential for increased disease transmission. Culling can disrupt social structures within animal populations, leading to increased movement and interaction among animals. This can facilitate the spread of diseases, both within wildlife populations and between animals and humans.

While the ethical and ecological implications of culling are significant, proponents argue that it can be a necessary measure in extreme circumstances citing a starving population. This argument ignores the human population explosion in Zimbabwe and Namibia. If this trend continues, no wildlife will be left in the near future. Wild animals are not farm animals. Wild animals living in their natural habitat are a driving force in the booming tourism industry of these countries.

To effectively address this complex problem, sustainable solutions that consider both human and environmental well-being are essential. Long-term solutions should focus on sustainable wildlife management practices and addressing the root causes of food insecurity. Measures such as improving water management systems, investing in drought-resistant crops, and enhancing community resilience to climate change can provide more sustainable and humane alternatives to culling.

Namibia and Zimbabwe should also develop policies to deal effectively with their population growth. It has been shown that increasing the education level of women is important for this. Thus, empowering women by improving women’s rights and access to education at all levels as well as increasing the legal minimum age to marry are essential for sustainably solving the problem of feeding their populations. This is far more effective and humane than killing elephants and other wild animals.