The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the inherent inequality and poverty prevalent in most countries throughout the world. This rings especially true in Latin America and the Caribbean, where the hardest hit by the pandemic have begun to fight back.

Rael Almonte Reyes, 25 August 2021

The COVID-19 pandemic took the world by storm in 2020, showing the flaws and deficiencies of economic and health systems around the world. From overwhelmed hospitals to lacklustre vaccine sharing schemes, it proved that even the most developed countries in the world will struggle with a pandemic if changes are not made to how we react to these crises. Nowhere was this message emphasized more than in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC). While on the surface it seems that the recovery has begun in Latin America, there will likely be medium and long-term implications of this pandemic over the next two decades.

In their 2021 report on the pandemic’s effects on Latin America, the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (CEPAL) stated that LAC will see a recovery from the 6.8 percent contraction of GDP and grow a predicted 5.2 percent in 2021, followed by 2.9 percent in 2022. While it is an improvement from negative growth, the rebound will not be sufficient to recover to pre-pandemic levels of output. Furthermore, data looking at labour markets, inequality and poverty paint a drastically different picture than those looking at growth. Between 2019 and 2020, the number of employed persons in LAC decreased by 24.8 million, of which around 13 million were women. Additionally, youth were some of the first to be laid off from their jobs.

The CEPAL report states that Latin America’s youth unemployment rate is extremely high, with rates ranging from 48.8 percent in Chile to 76.8 percent in Brazil. These numbers indicate how the poor and low-skilled laborers have been disproportionally affected by the pandemic. Although in 2021 the unemployment numbers began to recover, only 58 percent of the jobs lost during the pandemic returned. This has led forecasters to predict that the unemployment rate will ultimately increase from 10.5 percent in 2020 to 11 percent by the end of 2021. As many poor and low-skilled workers are employed via the informal sectors, it will be particularly difficult to have these persons “return to normalcy.”

This stagnant unemployment rate has exasperated another pertinent issue in LAC; poverty and extreme poverty. In 2020, the poverty rate was estimated to be around 33.7 percent, whilst the extreme poverty rate was estimated at around 12.5 percent. This accounts for about 287 million persons living in poverty and/or extreme poverty, making the pre-pandemic food security problem significantly worse. The CEPAL report states that an estimated 40.4 percent of the population was affected by food insecurity in 2020, despite food support policies implemented by governments throughout the region. This situation is further inflamed by the fact that food prices have been rising since 2018, with a substantive increase in 2020.

Governments in the region have attempted to remedy the distinct problems brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic by implementing massive expansionary fiscal packets, averaging 4.6 percent of GDP across the region. Although these fiscal commitments have contributed to marginally better responses to the pandemic in some states, overall, these policies have failed to address increasing poverty, food insecurity and inequality. Additionally, these commitments have contributed to a massive increase in public debt in the region, which increased from 45.6 percent in 2019 to 56.3 percent in 2020, while not addressing a rapidly collapsing tax base.

On top of the mass poverty created by the pandemic, inequality has skyrocketed in a region already known for some of the highest wealth disparities in the world. During the last decade, it was estimated that 71 percent of the region’s wealth was held by the richest 10 percent of the population. This gross level of inequality was made significantly worse during the pandemic, as indicated by the 2.5% increase in Gini coefficient in 2021. The Gini increase manifests itself as a $48.2 billion increase in the fortunes of the region’s 73 billionaires. Oxfam estimates that since March of 2020, an average of one billionaire was created every two weeks in the region, as millions fall into poverty and economic hardship.

A World Bank article written in June of 2020 stated that short term, living conditions, such as access to water, sanitation, education and healthcare, are highly dependent on where in the socio-economic ladder you stand. In the long term, the children of poorer persons will struggle, as access to virtual classrooms is often linked to socio-economic conditions, with the rich enrolling their children in well-funded schools and the poor forced to do the opposite.

These socio-economic conditions and the perception that the upper echelons of society are avoiding economic hardships are inciting social unrest throughout the region. From Chile to Mexico, people have taken to the streets to voice their concerns with the handling of the pandemic and its economic implications, although the largest movement has taken place in Colombia. The introduction of a tax system overhaul by the right-wing government of Ivan Duque sparked protests in Colombia in April 2021. The overhaul would have seen the state raise prices on everyday goods and services, including fuel and foodstuffs, and taxes raised for anyone making less than 2.6 million Colombian pesos ($684) per month.

While the proposed overhaul was the spark, the protests are the culmination of years of economic frustration. Even before the pandemic, many Colombians failed to earn the national minimum wage of 877,603 Colombian pesos ($227) per month. According to a 2018 OECD report, it would take 11 generations for a poor Colombian to approach the mean income in society — the highest number of 30 countries examined. Furthermore, the poverty rate has reached a boiling point, with more than 3.6 million Colombians falling into poverty since the start of the pandemic. The government’s response to these protests have caused the UNCHR and over 650 Colombian civil society organizations to call for an independent investigation on human rights violations by security forces.

Protests similar to those in Colombia are unlikely to subside until the socio-economic conditions of the protestors are improved. Not only has the COVID-19 pandemic plunged people further into poverty, making them more likely to push back against lethargic governments, but it has also made responding to the material conditions which drive the protestors more difficult. Ultimately, recovering from COVID-19 will be a herculean task for the Latin American Republics, but any plan that does not address rampant inequality is doomed to fail.

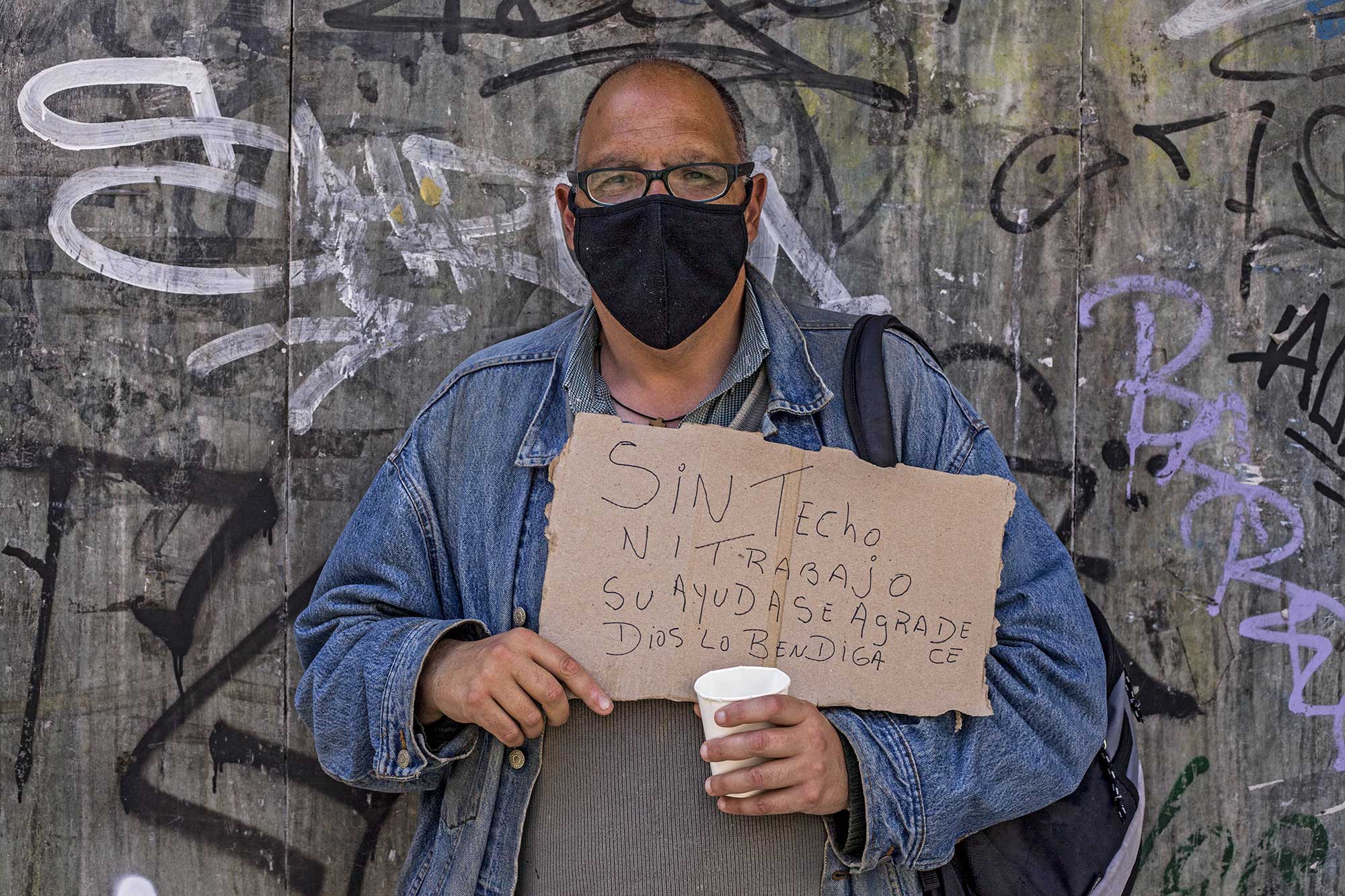

Picture: September 30, 2020, Buenos Aires, Federal Capital, Argentina: Unemployment reached 13.1% of the Argentine population in the second quarter of the year, with a rise of 2.7 percentage points compared to the first quarter, according to data released by the National Institute of Statistics and Censuses (Indec).The increase in the unemployment rate in Argentina occurred during a period of strong collapse of economic activity, amid the strict measures of social isolation dictated on March 20 by the Government of Alberto Fernandez to face the COVID pandemic. © IMAGO / ZUMA Wire

Other Articles Which Might Interest You

Rioting For Reform In Colombia