Weak state authority, easy access to firearms and indifference towards conflict resolution mechanisms has ensured that militant groups rather than the states are the predominant enforcing agents in diverse sections of the Sahel region. In order to find a viable solution, the cooperation of the involved stakeholders is necessary. Yet the question remains: will this be sufficient to bring peace and prosperity to one of the poorest regions and most vulnerable populations in Africa?

Michael Asiedu

7 July 2023

French version | Spanish version

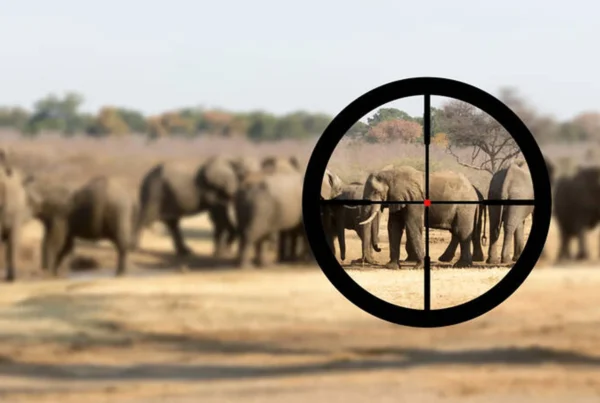

According to mainstream media, climate change is wreaking unimaginable havoc in the Sahel region, and the terms “climate wars” and “environmental wars” are becoming ubiquitous. While recognizing that conflicts can, and have been, exacerbated by harsh climatic conditions in the Sahel, there is evidence to suggest security rather than climate change is the region’s predominant concern.

The Sahel region which covers many countries such as Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Chad, The Gambia, Guinea, Mauritania, Mali, Niger, Nigeria, and Senegal, is home to a mixture of authoritarian rule, various militant or armed factions, as well as jihadist insurgencies. The region’s top leaders have already experienced multiple coups since 2020; two in both Burkina Faso and Mali, one in Chad and another in neighboring Guinea.

According to Alexander Clarkson, a researcher based in Kings College London, Islamist insurgent groups in Mali are already forming shadow governments. Human Rights Watch and International Rescue Committee reports also suggest that armed groups control about 40 percent of Burkina Faso. Hundreds of civilians and military personnel have died in Chad and Niger due to terror attacks. In 2022 more than 6000 people fled their homes in Gambia and Senegal due to fighting between Senegalese soldiers and separatists in the country’s Casamance border region. Nigeria battles with a militant Islamist faction called Boko Haram in its northern region, a security threat that transcends beyond its eastern border to countries such as Cameroon, Chad and Niger. Figures from the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project (ACLED) demonstrate a 200 percent increase in violence since 2020 in the region with over 4.5 million forced displacements.

This is the current security picture of the Sahel and the future does not look promising. It is aggravated by an assortment of jihadist groups who metamorphose almost weekly, including Ansar Dine, National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad (MNLA), Mouvement pour l’unification et le jihad en Afrique de l’Ouest (MUJAO) and Islamic State in the Greater Sahara who control varying parts of the Sahel, from Central Mali to as far as the Grand Bassam in Côte d’Ivoire. It is therefore unsurprising that the countries in this region feature prominently in the Norwegian Refugee Council’s “World’s most neglected displacement crisis” index.

According to the 2018 “Mapping Militant Organizations” report by the Stanford Center for International Security and Cooperation, these groups and their many offshoots tend to affiliate themselves to al-Qaeda and ISIL/ISIS. They aim to establish Sharia law in their areas of operation. Their main source of recruitment has been groups who feel politically marginalized in the region. These include mainly nomadic groups such as the Tuareg, Fulani, Tubu, Dossaak, and Zerma ethnic groups. The same ethnic groups are at the center of farmer-herder conflicts in the region. Disputes between farmers and herders often revolve around land use (grazing versus crop cultivation) and access to water and are therefore worsened yet further by harsh climatic conditions described in the 2022 United Nations “Sahel Predictive Analytics” Report.

Mitigation against climatic conditions of this severity requires a focused and comprehensive plan. However, such a plan will be unsustainable without simultaneously addressing Sahel’s security situation.

A combination of fragile state authority, access to firearms and a disregard for dispute resolution mechanisms has made jihadists, rather than state authority personnel, the enforcing agents in diverse sections of the region. Due to a lack of resources and government security personnel, in the remote border regions of Mali, Nigeria and Burkina Faso, the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara has stepped in. According to the 2023 Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime report, they have taken on the role of conflict resolution between herders and famers on cattle thefts, land use and crop destruction by cattle. A situation like this leaves much to be desired because with no uniform seal of authority, the state machinery is rendered useless.

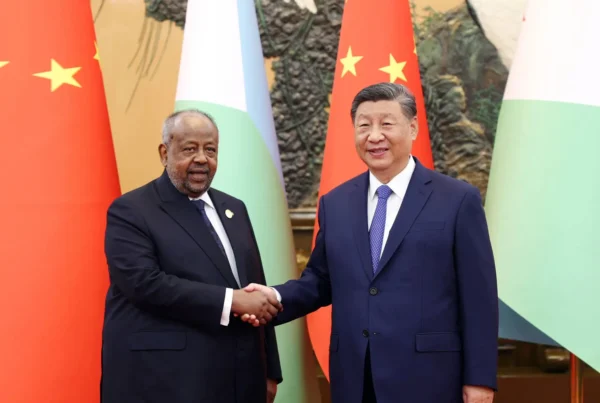

Exacerbating the jihadist power shifts in the Sahel is the failure of foreign powers who have geopolitical interests in the region to bring holistic security solutions. Over more than a decade, France, United States, the EU, and Russia have all attempted military interventions in the Sahel, both bilaterally and in joint efforts. Their goals were to shore up the security apparatus of individual states, curb jihadist insurgencies, and address the challenges of illegal migration to Europe, but they have had little success. In 2013 a joint-Malian French Military effort called Operation Serval, re-captured territories from Islamist militant groups in northern Mali, but many were subsequently regained by the same militant groups following the departure of French forces in August 2022.

In Chad and Niger, France established Opération Barkhane its largest overseas base with over 4500 soldiers deployed in counter-terrorism operations in the region. This initiative also involved Germany, the US and other Sahelian countries, but Mali is a notable omission due to French-Malian relations having soured leading to withdrawal of French forces from Mali. An additional satellite counter-terrorism initiative called Operation Sabre is based in Burkina Faso. Despite the presence of these counter-terrorism measures, recurring coups and security concerns in the region have not been sustainably curtailed.

Faced with these persistent security challenges, coupled with failed military interventions, perhaps the only plausible solution is a coordinated approach backed by political commitment from all ten countries in the region.

A blueprint already exists in the form of The G5 Sahel Joint Force (La Force conjointe du G5 Sahel “FC-G5S”). Involving five countries, Mauritania, Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger, and Chad, the two aspects which dilute its effectiveness are a lack of coordination and weak financial capacity. Furthermore, as the security challenges span the borders of all ten countries in the Sahel, it is imperative that stakeholders scale up the G5 to include every country in the region.

Will these stakeholders, including the respective Sahel governments, the African Union (AU), the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), the UN, along with western partners, be able to collaborate and provide the coordinated efforts required to prevent further suffering?