The concept of states giving their citizens a set amount of money has existed since Ancient Greece. Originating in Athens, the concept of Universal Basic Income (UBI) has spread across the globe in cutting-edge trials, producing results that are equally fascinating and contested. Since the COVID pandemic and subsequent economic insecurity, this concept is once again gaining traction, but will it survive its critics?

Eimhin McGann

24 July 2024

Arabic version | French version | German version | Spanish version

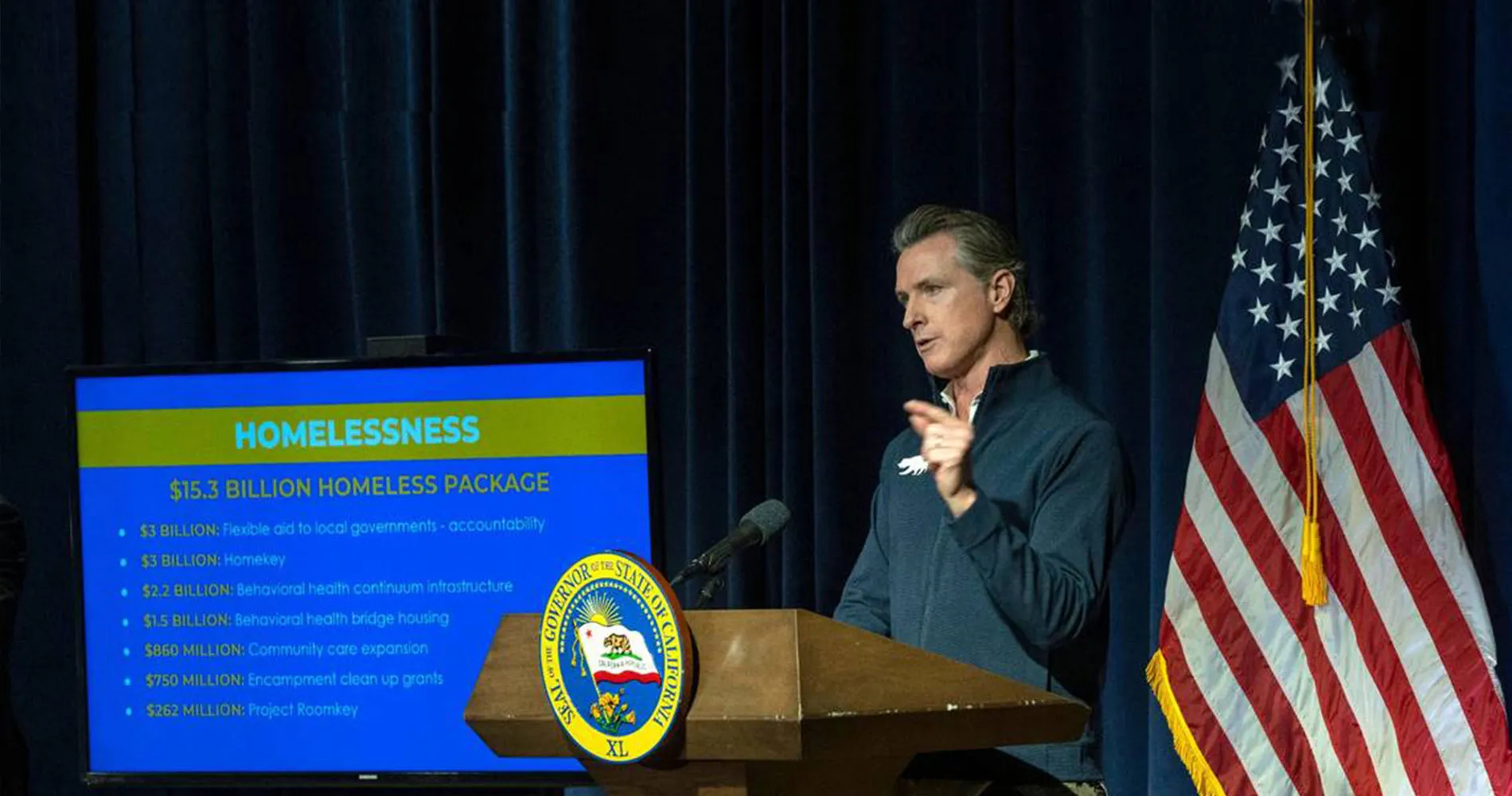

California is home to over one-third of the homeless in the US. With the median home value in California over USD 715 000, it is not surprising that many cannot afford housing or health care – even those who work fulltime jobs. In an ongoing effort to battle homelessness, California Governor Gavin Newsom (D) announced on 17 July 2024 the release of up to USD 3.3 billion in competitive grant funding to provide health care for the homeless and poor including for substance abuse disorders. California has spent USD 24 billion on the homeless since 2019. Yet homelessness has increased fivefold in this period to over 181 000 and California has spent the equivalent of USD 160 000 per homeless person over this time period. Could a new approach ease California’s homeless crisis?

The concept of Universal Basic Income (UBI) has existed for thousands of years, with researchers suggesting that the first example of UBI existed in the ancient Greek city state of Athens, which used revenues from city-owned mines to provide Athenian citizens with a small income. UBI was described by English philosopher and stateman Thomas Moore in his 1516 book Utopia, where he wrote that an ideal government would provide a basic income to all its citizens. Now, in the 21st century, the concept of UBI is being revived.

The main goal of every UBI trial across the world has been to create what Michael Tubbs, Mayor of Stockton, California, describes as “a floor to stand on”, meaning those below the poverty line can begin to build a better life for themselves without having to worry about covering bare necessities, such as rent and food payments.

Tubbs and his coalition of “Mayors for a Guaranteed Income” are advocating for a guaranteed income of “direct, recurring cash payments”, claiming that such income will “lift all of our communities, building a resilient, just America.”

One US pilot, the privately funded charity “In Her Hands” based in Atlanta, Georgia has been giving cash specifically to Black American women, who have to prove that they earn “two times the federal poverty level or less – or 29,160 USD for a single person”. Tubb’s view is that UBI can act as a way for poorer people to enjoy financial stability, resulting in physical and mental health benefits.

Various UBI pilots from around the globe have produced promising results regarding the amelioration of poverty.

From June 2011 to November 2012 the state of Madhya Pradesh, India, provided a monthly payment of 4.40 USD which equated to 20-30 percent of the income of families classified as “lower-income”. Recipients reported physical and mental health benefits, and additionally, 60 percent of women interviewed said that the UBI had empowered them to have a source of income independent of their male relatives.

A UBI trial in a small region of Namibia, reported that a modest monthly payment resulted in drastic reductions of child malnutrition and crime rates and an increase in school attendance.

Benefits are not just reported from pilots in developing countries. In a Finnish study a UBI group reported an average life satisfaction score of 7.3 out of 10, in comparison to a score of 6.8 reported by a non-UBI group.

This begs the question, why has UBI not been more widely adopted?

According to the Stanford Basic Income Lab, there are five defining characteristics of the modern version of UBI. A recurring payment (weekly, monthly, etc.), a cash payment, universal (meaning not targeted to any specific population), paid to individuals rather than households or any other social grouping and unconditional (meaning it has no work requirements or other prerequisites).

A report from Bloomberg covering UBI pilots from 20 US cities found that “Most beneficiaries were single, had kids, and were people of color”, which contradicts Stanford Basic Income Lab’s definition of universality. However, in Ancient Athens where UBI was given solely to “Citizens”, only a privileged few received it because the title of Citizen was denied to slaves, women and low-ranking men. Therefore, even then, it was not actually “Universal”.

This is but one of many issues with the UBI. While the basic concept is easy to understand and utopian in nature, determining its value by weighing up the cost of implementing UBI against its benefits remains much more difficult.

Evidence of UBI success has tended to focus on emotional changes such as peoples’ feelings about their mental health, levels of stress and satisfaction with life, all of which are subjective. The costs of implementation, including the demands on the tax-payer, are by contrast, quantifiable, objective and therefore easier to utilise when challenging a UBI scheme.

Another problem is the gap between rich and poor. A UBI trial in Texas has been declared “unconstitutional” by the attorney general, who has taken his case to the Supreme Court of Texas. Anti-UBI lobbyists are financed by billionaires like Richard Uihlein, whereas UBI recipients are less likely to have funds to fight a court case.

Furthermore, wealthier segments of society are concerned with the issue of reciprocity. If UBI is financed by taxation, those who pay more taxes, voice grievances that they will be paying for benefits they do not receive.

Many US welfare programs like TANF (Temporary Assistance for Needy Families) have work requirements attached to them but UBI payments are unconditional. Consequently, UBI raises the question, “Why should some people who work and pay taxes, fund the lives of those who don’t work?”

In a UBI trial in Catalonia, Spain, residents have been receiving UBI payments regardless of income level, which has led to the argument that UBI payments to the rich are a waste of state resources. If the goal of UBI is to prevent poverty, then why should those already enjoying financial security be given more?

UBI trials conducted so far have featured small numbers of people and short timeframes. The largest in Europe is ongoing in Catalonia, which started in January 2023 and is set to end in January 2025, with only 5000 participants. Evidence is therefore relatively limited, but running large-scale trials may be prohibitively expensive.

Some are concerned that UBI could be used to cut funding or entirely remove pre-existing welfare state benefits. In 2011, Iran introduced an unconditional cash payment equating to 20 percent of the average income, but simultaneously removed state subsidies on food and utilities. Many, especially those on the poorer side of society, fear losing the support they currently receive, in exchange for a new system of welfare that, as yet, has not been extensively tested. They worry that a new UBI-based system may not work effectively, or maybe even lead to them being worse off.

While there are populations who could benefit from UBI, including those in developed countries who risk losing their jobs to automation, the numerous questions of universality, robust evidence, social justice and large-scale financing may end UBI before it begins.