2024 marks the 150th anniversary of the opening of the Wiener Zentralfriedhof (Vienna Central Cemetery). The Vienna Central Cemetery is one of the largest cemeteries in the world, with over three million burials. The cemetery is famous for the “graves of honor” of many famous composers, actors, artists and politicians. The Viennese combine a paradoxical fascination with death with a joyful celebration of life. Today, the cemetery is a serene environment that attracts visitors for both historical exploration and leisurely strolls among its lush greenery and impressive monuments.

Alexandra Winterstein

12 December 2024

German version

When leaves turn orange and yellow, when trees are brown and bare, many turn inward. It is no wonder that many cultures choose to honor the dead in late autumn. Traditionally, this is the time to commemorate one’s ancestors. Cemeteries and burial grounds the world over invite us to visit our loved ones in these courtyards of peace.

This year marks the 150th anniversary of the opening of the Wiener Zentralfriedhof (Vienna Central Cemetery). To commemorate this date, Friedhöfe Wien GmbH (Vienna Cemeteries GmbH) organized a series of exhibitions and events, reflecting the rich heritage and significance of the Zentralfriedhof to its citizens.

Karl Borromaeus Church © Pixabay

Karl Borromaeus Church © Pixabay

The Vienna Central Cemetery is the third largest in Europe, after Hamburg Ohlsdorf, and Brockwood Cemetery in London. Three million people have been buried in 330,000 graves to date and “there is still plenty of space”, according to the Vienna Cemeteries press office. The diversity of its nature is impressive: 170 animal species co-exist among 70 types of fungi and 200 plant species, some of which are on the endangered species list. Deer stride soundlessly among the deceased.

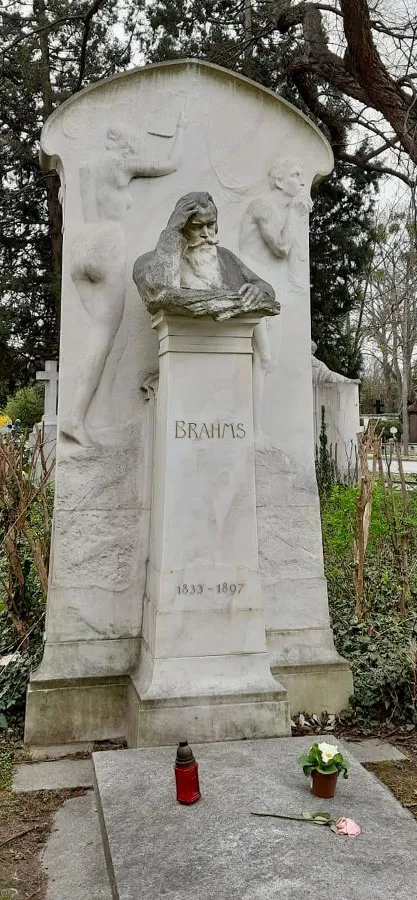

Grave of Johannes Brahms

Grave of Johannes Brahms

Grave of Udo Jürgens

Grave of Udo Jürgens

Grave of Johann Strauss (son)

Grave of Johann Strauss (son)

Grave of Hugo Wolf

Grave of Hugo Wolf

The Vienna Central Cemetery is more than just a cemetery. It is a reflection of the city, its citizens and history. The burial ground covers an area of 2.5 square km, which is more or less the same size as Vienna’s city center. The Central Cemetery is the final resting place of many of Austria’s famous natural and adopted sons and daughters: to the left of the main entrance at gate 2 lie the graves of the composers Ludwig van Beethoven, Franz Schubert, and Johannes Brahms, while Arnold Schönberg, Robert Stolz and Curd Jürgens rest in Group 32C. Other celebrities include Johann Strauss (father and son), Karl Renner, Otto Bauer and Victor Adler (politicians), Friedrich Torberg, Arthur Schnitzler (writers), Viktor Frankl (psychologist), Hans Moser, Helmut Qualtinger, Hedy Lamarr (actors), Adolf Loos (architect), and of course, Falco (enfant terrible, rock star).

The Central Cemetery was born out a grave need. As Vienna’s population grew in the middle of the 19th century, the capacity of the major cemeteries outside the city center reached its limits. As a result, in 1866, the municipal council of Vienna decided that a new “central cemetery”, a burial ground that was to accommodate all of Vienna’s dead, regardless of religion or denomination, should be built. A competition was held to design the cemetery grounds, which was won by the German garden architects Karl Jonas Mylius and Alfred Friedrich Bluntschli.

The poetic beauty and artistic grandeur of the Viennese metropolis of the dead was characterized above all by the graceful Art Nouveau buildings designed by the Austrian architect Max Hegele. By 1910, the Vienna Central Cemetery was enlarged with the construction of the sublime main portal of the second gate, the two halls by the main portal and the Church of St. Borromäus. This impressive cemetery church rises with its monumental dome like a silent sentinel over the cemetery grounds.

It is often said that the Viennese have a special relationship with death, Peter Ahorner writes in his new book “Vienna and Death”. In an interview with the publishing house, he says that “Vienna’s Central Cemetery is almost a place of pilgrimage – and not just for the deceased. Death is viewed here with a kind of relaxed humor that is unique in Vienna. I wanted to capture this morbid fascination, the Viennese coziness, even at the very last farewell. It’s the most charming way to look the inevitable in the eye.”

The Viennese, he says, laugh about the things they can’t change and use black humor to deal with the unpleasantness of death without dodging the seriousness of the situation. A morbid kind of brutal candor: more friend than foe, and death as the only true justice, the great equalizer.

This might be because Vienna seems to have invented the concept of the theatrical death experience. The Viennese were professionals when it came to funerals. A crowning finale was important even for the most modest of lives. To get “a schene Leich”, a stylish, dignified funeral with many mourners, people paid into savings clubs or indebted themselves. A new, flourishing funeral industry was born, and at its epicenter, was the Central Cemetery.

For sure, people were inspired by the splendor of Baroque aristocratic funerals. In the case of the ruling Habsburgs, this was demonstrated by elaborate, pompous coffins. It began in the eighteenth century, during Maria Theresa’s reign, where burials were carried out with “pomp, splendor and pageantry”. The “Pompfüneberer”, a dialect term for morticians, is derived from the French “pomp funebre” = pompous funeral; morticians dressed in velvet, black gala vestments and two- or three-cornered hats. The last journey was to be dignified and magnificent, as if this would assure you a better place in heaven.

Over the years, the Vienna Central Cemetery has been continuously extended: in 2014 a funeral museum opened to show exhibits about historic funerals and the cult of the dead in Vienna. All of Austria’s deceased federal presidents since 1945 are commemorated in the presidential crypt in front of the cemetery church, the Karl Borromäus Church. Today there are about 950 memorial graves, which attract visitors from all over the world.

In order to improve the accessibility of the cemetery, a horse-drawn tramway was built, which was replaced in 1901 by an electric street car. Since 1907, this line is known as number 71 of the Vienna streetcar public transportation system. The “71” is deeply rooted in Viennese culture and is often mentioned in anecdotes and songs. If someone “takes the 71”, it means that someone has passed away.

For those looking to reflect and wonder on a cold winter day: take the tram 71 and walk through the grounds. A mystical elegance entwines the entire cemetery terrain, like ivy lovingly entwines old gravestones.