The EU’s Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) is responsible for one-third of the annual EU budget. Member States had previously agreed on a reform focussing on sustainable farming practices. The Ukraine crisis has made food security in the EU a central concern for Member States. New proposals by Austria’s Agriculture Minister ahead of the EU Agriculture and Fisheries Council on 21 March to cultivate fallow land and introduce a new EU Protein Strategy have gained the support of twenty Member States. The EC is currently preparing a proposal along these lines. Green lobbyist are strongly opposed to these new initiatives.

Bruce McMichael, 22 March 2022

An online search for ‘European Union’ and ‘Common Agricultural Policy (CAP)’ yields a vast array of critical news articles, dozens of civil society websites suggesting perceived flaws and finally calm, considered bureaucratic explanations from the European Commission itself.

The CAP is responsible for one-third of the annual European Commission (EC) budget. It is thus no surprise that its very existence is in a constant state of financial, political and, for farmers and other funding recipients, commercial and increasingly environmental stress. Previously CAP negotiations and EC policy is a moving away from increasing production to focussing on the principals of the Green Deal – sustainability, social responsibility and climate and environmental awareness.

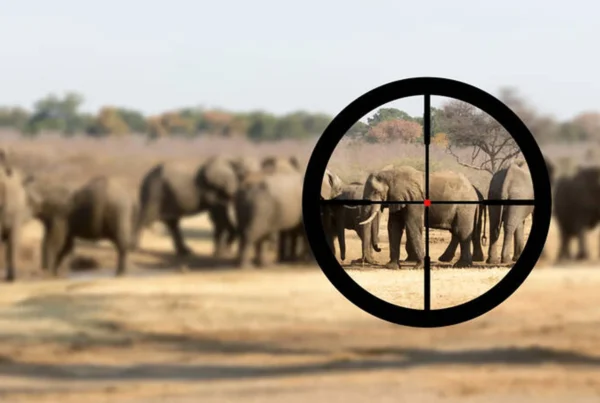

While these principals are important long-term goals that will shape the future of agriculture across Europe, food security will also play a role. The ongoing conflict between Russia and Ukraine has disrupted the flows of many commodity materials from fertilizers and grain to hydrocarbons and metals. Together, Russia and Ukraine account for 30% of world trade in wheat, 32% of barley, 17% corn and over 50% of sunflower oil and seeds. The price of wheat as doubled since the start of the war in Ukraine.

Ahead of the Agriculture and Fisheries Council Meeting on 21 March in Brussels, Austrian Agriculture Minister Elisabeth Köstinger has launched an EU initiative aimed at using fallow land to make up for the loss in production from Ukraine. Köstinger is demanding the release of the land set aside as part of the EU’s agricultural policy. If this proposal is approved, an additional four million hectares of land could be used to cultivate wheat in the EU. Moreover, Austria has also presented an initiative for a European Protein Strategy. Köstinger wants European farmers to grow more protein (rapeseed and soybean). This proposal has garnered wide support among Member States and has been criticized by green activists.

Throughout its 60-year existence, the CAP has been plagued with controversy. Its perceived weaknesses were a key factor in the UK leaving the EU. Conceived in a very different time, CAP is a partnership between agriculture and society, and between the EU and its farmers. Since 1962, CAP has supported a single market for EU agricultural food products while maintaining some of the world’s highest safety and environmental standards and ensuring affordable prices. Without CAP payments many farms would not be able to survive. In France alone, 47% of the farmers’ income came from the CAP.

The three regulations that make up the CAP reform package were signed by both the European Council and the European Parliament and were published in the EU’s Official Journal on 6 December 2021. The new policy will apply in full in 2023 up to 2027. Negotiations to finalise the new CAP are scheduled in the coming months for Member State implementation.

By 2030 the EC wants natural spaces, from forests to soil, to capture 310 million tonnes of CO2 – a dramatic turnaround from the previously declared target of 225 million tons they were expected to sequester under a business-as-usual scenario.

In order to achieve these targets, CAP must be shifted from the current hectare-based system of funding to a system rewarding sustainable farming practices. This includes incentivizing landowners to take part in so-called ‘carbon farming’, where farmers and foresters introduce measures, such as crop rotation and reforestation, to increase the amount of captured carbon dioxide.

Economic and agricultural analysts warn of food price rises driven by farmers and cooperatives who regard the proposed new CAP with suspicion. Producers are fearful that a focus on ‘sustainable’ food production will negatively impact their traditional farming practices and outcomes. The war in Ukraine will exacerbate this trend.

Another charge levelled at CAP is that, by ignoring accepted rules of supply and demand, the policy is hugely wasteful. It leads to overproduction, forming mountains of surplus produce that has previously included cereal, rice, sugar, wine and milk products that are destroyed or dumped in developing nations.

The unforeseen consequences of the existing CAP are that production costs of certain agricultural commodities such as milk have caused farmers in a number of developing countries to deal with artificially low milk prices. For example, multinational companies operating in countries such as Senegal and Ghana are importing cheap (subsidised) milk and milk powder, which distorts local market dynamics.

In early 2020 a group of MEPs sought a volume reduction in the dairy sector in order to avoid disrupting such markets, increasing milk storage in the EU or destroying unsold milk, but little has been achieved. Subsidised milk production has also pushed prices down across the EU, raising the spectre of milk lakes created for subsidies not for demand.

The Farm to Fork Strategy is at the heart of the Green Deal approved by a wide majority of Members of the European Parliament (MEP) in October 2021. It aims to make food systems fair, healthy and environmentally friendly. But many remain wary of the unintended consequences of this strategy. Global advocacy group Slow Food International suggests that currently any reformed CAP will continue to reward those with the largest land holdings rather than smaller, more bio-diverse farms, such as mountain sheep farms.

Some European farmers are raising concerns that the Farm to Fork Strategy may lead to an off-shoring of our food and agricultural production to countries outside of the EU. Issues that are dividing the continent include plans to reduce pesticide use such as neonicotinoids and glycophosphate as well as alternative technologies such as new breeding or genomic techniques. Big pharma and agricultural conglomerates are lobbying for these technologies at the EU level.

After 60 years, CAP still has the power to surprise its supporters and detractors. With environmental concerns changing the paradigm, CAP is bringing green agendas to the negotiating table. Yet the Ukraine crisis has thrown a wrench into the green equation.

Over the past couple of decades, governments across Europe have downgraded food security, which no longer had a high priority. The conflict in Ukraine has changed priorities for the CAP reform. As food and fertilizer prices rise, negotiations in Brussels and across Member States suddenly have a huge new issue to deal with, namely, securing affordable food for their citizens. The CAP reform will need to balance food security with sustainability, as well as social and climate change issues.